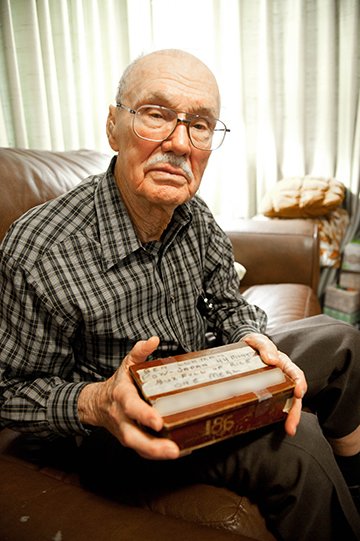

Benny Lohman holds a wooden daily ration box given to him by his Japanese captors. This box, a couple of spoons (one he made), a mess kit and a canteen cup are among his few possessions while a Japanese prisoner of war from 1942 to 1945. Photo by Joe Bollig.

St. Agnes parishioner recalls his time as a Japanese POW

By Joe Bollig

joe.bollig@theleaven.org

KANSAS CITY, Kan. — Not just anyone can call Benjamin Lohman a “jarhead.”

“Wait a minute,” said the 95-year-old Lohman, a member of St. Agnes Parish in Roeland Park.

“You’ve got to be in a good squad with a good first sergeant before you can call anyone a jarhead. If you’re called a jarhead, you’ve either got to fight or . . . think. Take your pick.”

There aren’t many left like Benjamin “Benny” Lohman: a genuine China Marine, defender of Corregidor Island, “guest” of the Japanese emperor.

In other words, a survivor.

Many men came back from World War II and tried to forget, to get a job and raise a family. Mostly, they succeeded. But it wasn’t easy. Some things just can’t be forgotten.

Lohman was born and raised in Lansing, which seemed small to him. By the time he was 22, the country still hadn’t made it out of the Great Depression.

“I was shoveling coal at 10 cents a ton, and that ain’t much,” he said. “And I got tired of doing that. I heard someone say, ‘Hey, the Marines are paying $30 a month,’ so I went to Kansas City and signed up.”

The young Kansan had a cousin in the Marines. If his cousin could do it, so could he. And, oh boy, wouldn’t it be great to see the world?

So on Jan. 5, 1940, Lohman went into the U.S. Marine recruiting office in Kansas City and signed up. Only a few days later, he was on a three-day train trip to San Diego. There, he learned to drill and “prepare to be shot at” in a war.

“And don’t be crying about every little thing that comes down the road,” said Lohman.

Six weeks later, he and a whole platoon of newly minted Marines were hustled aboard the USS Harrison and sent directly to Shanghai, China. He was in Company E, 2nd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment.

“We didn’t even make a liberty in the United States,” he said.

Powder keg City

Shanghai was one of the most unusual cities in the world in 1940. Nominally Chinese, thousands of Americans and Europeans lived in the International Settlement.

The International Settlement, created after the Opium War of 1842, was one of several Chinese ports that Western powers forced open for trade.

The city was basically divided into French, British and American sections, or concessions, although many other nationalities claimed enclaves in the American Concession: German, Italian, Russian

and Japanese. Old Shanghai was Chinese.

This Babylon on the Huangpu River was known both for its elegance and decadence. Startling contrasts of different cultures — and extremes of wealth and poverty — existed cheek and jowl.

The various nationalities formed a municipal government that provided the services needed for a major city. They even had their own small “army,” supplemented by American and British troops.

“Our regiment protected American lives and property in Shanghai, from robbers, thieves and anyone else who wanted to do something against Americans,” said Lohman.

The U.S. Marine Corps in 1940 was smaller than the New York City Police Department, so Marines considered themselves an elite brotherhood. In that exclusive world, the Shanghai duty station was considered a choice assignment.

“When you got to China, there was an exchange rate,” he said. “It varied from [16 Chinese Yuan to One American dollar], so we were millionaires.”

One of Lohman’s complaints, however, was that it was difficult to get to Mass on Sundays.

“I was scared to ask the first sergeant,” he said. “The other guys would think you were getting off. [First sergeant] would have to relieve someone so you could go to Mass, and they didn’t like it.”

Storm clouds

Japan, which had been waging an incremental war against China for years, finally invaded Shanghai in 1931 and dominated the city. As the Japanese grew ever more aggressive, relations with the United States deteriorated. Occasionally, the Americans and the Japanese would trade shots.

But it was not until Nov. 27, 1941, that the 4th Marines were withdrawn from Shanghai and were shipped to the U.S. naval station Olongapo in the Republic of the Philippines.

They arrived there on Dec. 2 and, five days later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The Philippines were attacked the next day.

“We were getting our gear squared away and a place to stay when word came down, ‘Pearl Harbor has been bombed. We are at war,’” said Lohman. “That’s when things really started to get bad. Nobody believed how bad it was.”

On Dec. 26, the 4th Marines were deployed to Corregidor Island at the mouth of Manila Bay, known as “the Gibraltar of the East.” The Marines, who only numbered about 1,500, were the primary defenders of the tadpole- shaped island. After the fall of the Bataan Peninsula, they were joined by a motley assortment of American and Filipino military personnel.

They didn’t have enough food, ammunition, weapons, medical supplies — or anything else.

Corregidor was under constant air attack and naval bombardment. Finally, a Japanese invasion force landed on May 5, 1942, and Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright surrendered the next day.

Guests of the emperor

The first order of business was the destruction of the Marines’ weapons. Some men tried to escape Corregidor on the tide, but they forgot that the tide could bring them back. Those who had escaped were recaptured, all covered with oil from sunken ships, and shot.

The Japanese took the remaining Americans to Bilibid prison camp in Manila.

“We didn’t realize how serious the Japanese would treat us,” said Lohman. “We knew what prison in the U.S. was like, and we thought it would be something like that, but it wasn’t. [The Japanese] didn’t care if you lived or died. If you were sick, you didn’t get no medicine. You really had to scrounge for yourself.”

American prisoners were marched out every day to other camps. One day, Lohman took a daring chance.

“I was sitting there looking at everything, trying to figure out something. So I just jumped into a line of troops and marched out,” he said. “They didn’t count. Of course, when you got to where you were going, you got counted.”

Lohman ended up in Cabanatuan One prison camp. It, too, was a rough place.

“It was bad, everything was bad,” said Lohman.

There was disease, bad water, malnutrition, hard work in rice paddies, and brutal treatment by guards. The prisoners lived in huts. Although he didn’t, some prisoners would steal from each other to survive.

One of his worst memories is how he saw a man, weakened by disease, fall into a latrine and drown.

This happened more than once, and the Japanese would shoot would-be rescuers.

In October 1944, more than 1,600 prisoners, including Lohman, were transported from Cabanatuan to Japan in “hell ships,” so called for the awful conditions aboard.

Lohman survived the trip, and was sent to an Osaka shipyard and put to work making oil tankers as part of a prisoner rivet team. There, an elderly Japanese civilian worker committed a rare act of kindness.

“He never said a word or got mad,” said Lohman. “One day, he brought me a pair of split-toe shoes. (The sandals Lohman was wearing were falling apart.) He gave them to me and didn’t say a darn word. I just want to thank that guy. He’s probably in heaven. I never did see him again.”

Lohman was eventually sent on from Osaka to a copper mine at Akenobe, or Osaka Number 6B. The prisoners working there were American, British and Australian.

The camp was opened on May 16, 1945, according to an investigation for the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. The work was hard and sometimes the prisoners were slapped around, but there were no atrocities.

In his postwar memoirs, Japanese camp translator Kazuo Kobayashi recorded the camp commander surrendering his sword to the ranking American on Aug. 17, 1945.

“The Japanese commander of the camp . . . he couldn’t hardly speak English,” said Lohman. “He got up and said, ‘We will now be friends. The war is over.’”

Once word of the Japanese surrender spread, the former prisoners were eager to put the prison camp behind them. Lohman remembered one American Army dentist, however, pausing long enough to scoop up all the camp records he could find before they could be lost or destroyed.

The rescued men commandeered a train in the town below the mine and rode it all the way to the port city. There, they found Allied ships and personnel.

“I went aboard one of those ships and they treated me like a king,” said Lohman.

A British medic on the ship treated his badly infected leg, and probably saved it — if not his life.

Lohman went home to Lansing, got married in 1946, and eventually had six kids. He had a 29-year career, ironically, as a state prison guard.

“It was a strange experience,” he said, of his life as a prisoner of war. “You put up with so darn much. . . . Most of us did depend on our faith, the faith our mothers and fathers taught us when we were young. You really did depend [for survival] on your faith.”