by Marc and Julie Anderson

mjanderson@theleaven.org

As Americans around the country celebrate Veterans Day with parades and patriotic speeches, the sacrifices of the actual soldiers involved rarely end when the crowds disperse.

For many, the battles continue quietly for years — through sleepless nights, unseen injuries and the haunting memories of war that can become too heavy to bear.

Right here in the archdiocese there are hundreds, if not thousands, of servicemen, women and veterans, thanks to the presence of Fort Leavenworth, two major US. Department of Veterans Affairs systems and Forbes Field Air National Guard Base in Topeka. Just outside archdiocesan boundaries lie Fort Riley and a Veterans Home.

Thus, the challenges veterans face weigh heavily on even those close to home as the nation prepares to honor them Nov. 11.

In preparation for this Veterans Day, The Leaven interviewed several Catholic veterans whose work found them ministering to their fellow soldiers in various capacities. What they learned about the trauma their fellow soldiers faced and how some still struggle to cope with its aftermath makes for challenging — but necessary — reading.

Warning: This article contains accounts of violence that some readers may find disturbing.

Between 2012 and 2022, an average of 17 veterans took their own lives each day.

Those numbers are official: They come from a 2024 report from the VA.

That same report said the country has lost at least 120,000 veterans by suicide since 2001 — more than total the number of Americans killed in all conflicts since the Vietnam War.

Those are the ones we know about.

******

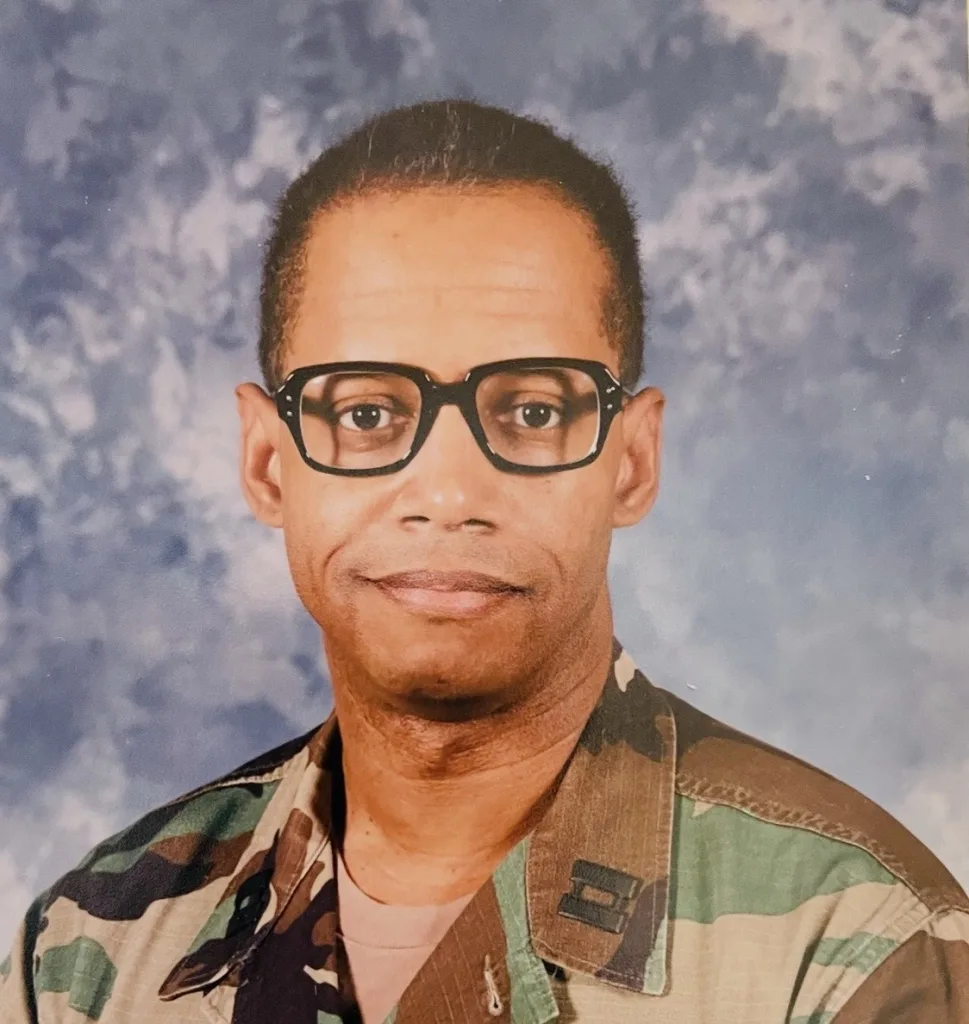

A Vietnam veteran, Father Anthony Williams left the military in 1975 to enter the seminary, later returning to military service for 10 years as a chaplain prior to rejoining archdiocesan ministry. One challenge, he said, veterans face in their return to civilian life is a loss of closeness that is almost irreplaceable.

“They’re in a close unit, squadrons and so forth, the infantry, too, and they bond,” said Father Williams. “They travel, they have mission goals. . . . They’re always working to give their best in service to their country, and so they bond with military guys who are there.”

Sometimes translating their military training into civilian careers might turn out to be challenging. For example, an Army helicopter pilot might not find a job in civilian society as easily as a mechanic.

There can be relationship issues, too, Father Williams said, in coming back to a family that “may have moved on and done a lot of things without the military member there. Then, he or she comes back and there’s not that relationship.”

Recalling his days in Bahrain, the former chaplain said that once security police came to the chapel where he was leading Good Friday services. He later learned an airman had jumped off a 10-story balcony.

“This guy had gotten a ‘Dear John’ letter from home. And so, he went into his depression and thought the worst and [decided] there’s no reason to live anymore,” he said.

Besides relationship issues, Father Williams said, there’s the actual physical trauma of war for the veteran who has seen action.

He recalled one young man from Iraq whose vehicle was hit by an IED that killed his buddy who was driving.

“[W]hen he got into the hospital, he was basically just almost catatonic. That’s how he was,” he recalled. “I can’t describe it. He laid there. He couldn’t talk. He was just existing.”

Besides physical injuries and emotional scars, Father Williams explained veterans often experience regret, remorse and nightmares for years — even decades — later. In particular, the aftermath of the Vietnam War has been hard on veterans who served there.

During that war, what seemed to be innocent Vietnamese children were sometimes used to kill American servicemen, throwing grenades or shooting at them, leaving soldiers split seconds to decide whether to return fire.

“The soldiers had to do things and see things that were so traumatic and harmful to their psyche,” he said.

“So, coming back with [the memories of] that, when the Vietnam War ended and they came into Washington, D.C., and so forth, they were . . . generally known as baby killers. And that was the welcoming they got coming back into this country.”

That “welcome” didn’t help those veterans, Father Williams said.

Father Peter Jaramillo, SSA, pastor of St. Mary-St. Anthony Parish in Kansas City, Kansas, agreed.

“The war was a learning point for our country . . . particularly to help our nation to understand these various issues,” he said.

******

Angie Gabel, a parishioner at Most Pure Heart of Mary in Topeka and a mental health professional who serves guardsmen and veterans, agreed that the military culture has learned much about mental health in recent years.

“It’s OK to not be OK, and it’s OK to seek help, and it’s not a career-ender,” Gabel said. But it has only been in the last decade or so that the military began offering more robust mental health resources.

That’s important, she said, as often veterans don’t want to burden their loved ones, especially if the veteran has seen fire. Veterans need to be surrounded by people who support them.

“If you’re not in an area that absolutely gets it, you are suffering alone. And so, you think about your suffering alone,” she continued. “You isolate. Then, all you have is your thoughts and your trauma. You go down those rabbit holes. Then, you add physical pain on top of that with medical concerns.

“It’s all just a disaster waiting to happen.”

A chaplain in the Kansas Army National Guard for 20 years, Father Peter was deployed three times, serving in Germany, Iraq and Kosovo. He, too, said military culture has shifted with regard to mental health.

While deployed, he said, soldiers can experience loneliness, hopelessness, helplessness and guilt, among other emotions. They might be trying to navigate personal situations, too.

For example, a soldier’s marriage might be in crisis, but that doesn’t stop the deployment. Meanwhile, maybe the soldier’s mother is dying, too.

“We really need to be aware, and command [staff] needs to know, what’s going on because [soldiers have] got a lot on their shoulders,” he said. “They’re going to go into a danger zone. They’re going to be asked to defend the nation and they’re going to carry a weapon.”

******

While the military trains everyone on suicide prevention, some challenges don’t surface until veterans return home.

That’s why the military works through reintegration processes about two to three months before deployments end.

“And so, what does that mean?” asked Father Peter. “Well, what are some of the circumstances? If you’ve been out of your home environment for a year and you’ve been in a hostile environment, you’ve been geared to respond, react, etc., in a certain way.”

Ron Quigley, a member of St. Patrick Parish in Corning and an Army combat medic in the 1990s, agreed, saying his deployments caused a lot of stress, some of which he carried home.

When he returned home, Quigley said, and would go to restaurants, he’d always sit so that he could see the door.

“You’re checking things in the civilian world that you would do in the military,” he said. “Like, I would tell [my wife] Brenda that I don’t want to go there because it’s what you call a choke point or something like that or a field of fire or whatever.”

Quigley’s father-in-law Roger Adams, also of St. Patrick Parish in Corning, echoed similar thoughts.

Adams was also a combat medic in Vietnam.

“Whenever things would start getting intense, somebody would get wounded and I’d have to take care of them,” he recalled. “I kept busy that way and didn’t, you know, think about it.”

Nighttime was different.

“The whole time I was over there at night when I would go to sleep, I would dream about being home,” he added. “When I came home, at night, I started dreaming about being back over there. When I’d wake up, I would recite the 23rd Psalm just to get my mind on something else.”

******

Retired veterans can sometimes struggle with not only psychological wounds, but with moral injuries as well, said Chaplain (Col.) John Potter, a member of the Kansas Army National Guard and the state command chaplain.

“A moral injury could be just carrying out an order that you had doubts or questions about,” he said. “It could be someone in a tank who’s told to fire, you know — to shoot a building because there’s a sniper on the roof. And he said, ‘Is the building clear?’ ‘Yes, no one’s there.’

“But then, you find out later that there may have been a family or kids playing in the building. So that could cause a moral injury. You’re just following orders, you did what you were told to, but you had no idea what the consequences may have been.”

Besides moral injuries, the chaplain said, there’s broken relationships, the death of loved ones, job losses and financial woes. A loss of mission or purpose, along with social connections, can compound the situation. Retiring veterans have to look for housing, jobs and belonging in ways that they’re not used to.

Adams agreed.

“When you retire,” he said, “you have more time to think. . . . I think that’s why you see a lot of alcoholism and drug use in veterans — so they can probably forget it.

“I think one thing that helped me is that I stayed in the Army four years after I got home and I was around people that had been through what I had. We used to sit and talk. And you know, that helped quite a bit.

“The worst thing a veteran can do is to keep it inside of himself.”

How to help veterans

Traditional ways for Catholics to honor and support their nation’s military abound. From mentioning deployed service members in the bulletin or in the prayer of the faithful, to planning “Welcome Home” events when they return, there are many ways to show a service member he or she is cherished by their faith community. But a ministry of presence is perhaps even more appreciated by this vulnerable population — and sometimes that takes raising awareness. See below for some suggestions from those who have been there.

1. Avoid prejudging someone who is living on the streets.

It might be a veteran, Father Williams said, who is experiencing homelessness. Buy the individual a sandwich or a cup of coffee instead.

2. Practice nonjudgmental listening.

Gabel said veterans sometimes avoid attending church because they feel guilty for actions taken while they were in the military. “Those are the nightmares, the terrors, the visions they see daily when they close their eyes. They don’t need a church to foster that judgment because they’re already feeling it themselves.”

3. Bridge the gap.

Steve Harmon, a parishioner at Sacred Heart in Emporia, said a good place to start is with the faith. As a traditional soldier and a citizen-soldier, his 38 years of service in the Army and the Kansas National Guard have included overseas service in Afghanistan, Kosovo and Kuwait. “We all know the [Nicene] Creed, and we have the saints and we have prayer, and we have the experience of a shared faith. That’s a huge way to bridge the gap,” he said.

4. Start small and listen.

“Sometimes just starting a benign conversation can segue into a larger conversation. I don’t know how to tell you how to listen for it, but you pick up on stuff,” Quigley said.

Moreover, intentional listening involves asking open-ended questions, being comfortable with pauses and avoiding asking emotionally-triggering questions like how many people did a veteran kill in action.

5. Form a volunteer pool of drivers to take veterans to appointments, the store or Mass.

6. Remember that a kind word or smile can make a difference.

“Research shows if between the time of the idea [to take one’s own life] and the act, if there’s five minutes that you can stop and call someone or someone notices, that is life and death,” Gabel said.

7. Normalize conversations about mental health.

Churches can help by offering mental health training for interested parishioners or inviting in mental health professionals as speakers — especially those trained to serve veterans. In one-on-one conversations with veterans in crisis, don’t

shy away from the hard questions, like “Do you have a plan to kill yourself?”

8. Reach out to a veteran’s battle buddies.

“Veterans would much rather speak to a battle buddy than their spouse,” Gabel said.

9. Keep the 988 option 1 handy.

When calling 988, Gabel instructs military personnel and veterans to press 1. That way, they are transferred to a trained clinician with military experience, and that can mean the difference between life and death.

The article “Do We Honor Our Soldiers Each Veterans Day — Only to Leave Them Facing Their Biggest Battles Alone?” by Marc & Julie Anderson delivers a poignant yet critical reflection on how our annual Veterans Day tributes often mask the real struggles many former service members face: trauma, alienation, and inadequate support. What really stood out is the authors’ challenge to the national ritual of thanks. They argue that surviving combat is only half the battle for many, the war continues long after they leave the uniform. From isolation and broken bonds to the psychological scars of deployment, the piece calls for more than speeches and parades.