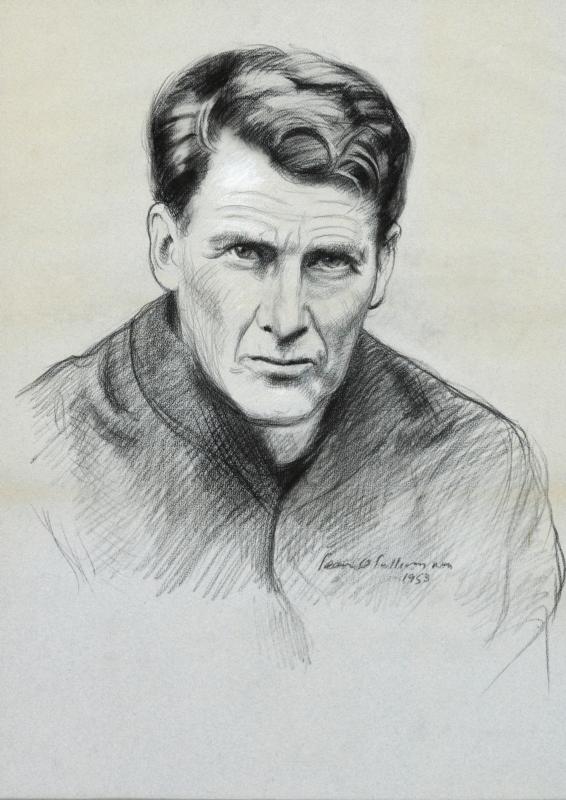

Jesuit Father John Sullivan is seen in this drawing by Irish portrait artist Sean O’Sullivan. Father Sullivan, who will be beatified May 13, was known as a healer. (CNS photo/courtesy Irish Jesuit Communications)

by Susan Gately

DUBLIN (CNS) — When Jesuit Father John Sullivan is beatified May 13, two archbishops — one Catholic and one Anglican — will present the solemn petition asking that the priest be declared “a blessed.”

That is unusual, but Father Sullivan’s life straddled two centuries, two traditions and two cultures.

Born in 1861, one of five children, John Sullivan grew up in privileged conditions in Ireland and Britain. He was raised in the Protestant tradition of his father, Sir Edward Sullivan, who rose to be lord chancellor of Ireland. His mother, Elizabeth, was a devout Catholic.

Father Sullivan later wrote of “a blessed childhood in a happy, loving home” although, at age 16, he suffered the loss of an older brother through drowning. In Trinity College Dublin, he excelled in his studies of the classics. He was an avid player of tennis and the card game whist and was dubbed “the best-dressed man in Dublin.” Society mothers viewed him as a major trophy in the matrimonial mart.

In 1885, the year of his father’s death, Sullivan went to London to study law. He traveled extensively, and even considered becoming a monk at one of the Orthodox monasteries on Mount Athos in Greece. A shy, remote figure, he was nonetheless popular and known for his kindness. His search for God is fictionally recreated in Ethel Mannin’s book “Late Have I Loved Thee.” In 1895, he traveled as part of a British government delegation to investigate a massacre in Adana, Turkey. A year later, at 35, he became a Catholic.

His reception into the Catholic Church marked a complete break with the life he had lived. Returning to his affluent home in Dublin, he stripped his room down to the floor boards and spent much time visiting the poor and dying. Four years later, he entered the Jesuits.

From the time of his ordination in 1907, reports of miraculous healings began. Cures for meningitis, St. Vitus Dance, breast cancer, tuberculosis, pernicious vomiting, infantile paralysis and many other illnesses were all attributed to his prayers during his lifetime. He willingly cycled long distances to spend hours praying at a patient’s bedside while working as a teacher in Clongowes Wood School in County Kildare, where the boys attributed his success more to his prayers than his teaching powers.

After his death in 1933, his graveside in Clongowes became a place of pilgrimage. The healings continued.

Jesuit Father Conor Harper, vice postulator of the Jesuit’s sainthood cause, said hundreds of miracles have been attributed to his intercession, many within living memory.

Neil Morton, former headmaster of the Enniskillen school where Father Sullivan was educated, says Portora school is “proud of being the only Protestant school in the history of Ireland that can boast of having a Catholic saint.”

But for Father Harper, Father Sullivan’s real greatness is that “he is a priest of the poor and the sick — that is why he is known.”