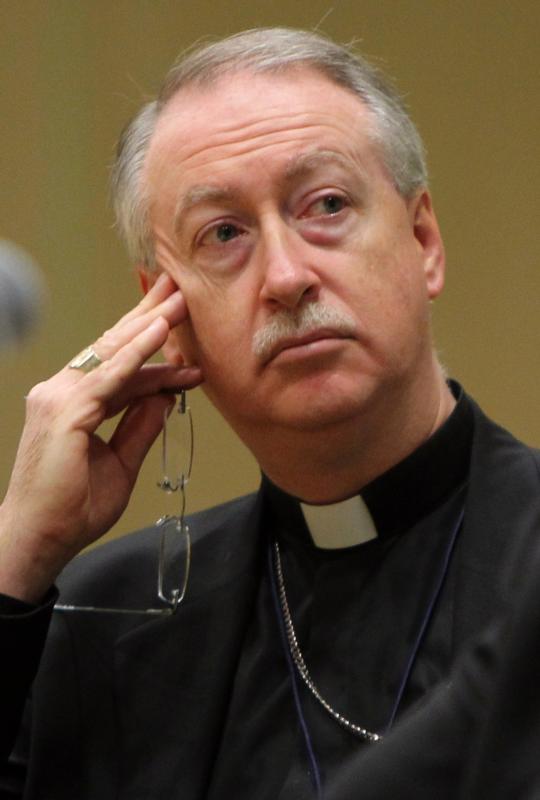

The specter of assisted suicide is leading aging people to “fear an institution that should be the last thing they should ever fear, a hospital,” said Edmonton Archbishop Richard Smith. Archbishop Smith is pictured in a 2010 photo. (CNS photo/Nancy Wiechec) See CANADA-ASSISTED-SUICIDE-SMITH April 13, 2016.

by Thandiwe Konguavi

EDMONTON, Alberta (CNS) — The specter of assisted suicide is leading aging people to “fear an institution that should be the last thing they should ever fear — a hospital,” said Edmonton Archbishop Richard Smith.

“But the strong feeling is, ‘If I can’t speak for myself, if I’m alone with no family members, are they going to kill me?'” he said April 5 at a talk at Edmonton’s Corpus Christi Church.

It is a question that “flows naturally” from the January Supreme Court decision allowing doctor-assisted suicide under certain conditions, the archbishop said. “This decision turns inside out the relationship between patient and doctor, patient and hospital; it undermines the trust that must be there.”

A series of talks across the Edmonton Archdiocese has drawn large crowds and raised poignant questions on euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.

The archbishop said the other “elephant in the room” is what the court decision has to say about family life.

Earlier, in a session with a group of seniors, Archbishop Smith heard how the elderly are feeling pressure to not be a burden on their children and on society.

“That’s where the so-called right-to-die slips into a duty-to-die,” he said.

In jurisdictions where physician-assisted suicide has been legal for some time, people were asked why they would seek it; they answered with avoidance of pain and suffering near the bottom of the list of reasons, while not wanting to be a burden was at the top, said Archbishop Smith.

“How does that even creep into people’s heads?” he asked.

Alicja Chandra, a volunteer at the Edmonton Pregnancy Crisis Centre, said it was easy to see that people were concerned about assisted suicide.

Chandra said she is also concerned about young people: how families can be torn apart by the pressure the legislation puts on people to “not be a burden” on their children, or the temptation of young people envisioning coming into an early inheritance.

“It may come to this — ‘I don’t need my parent anymore. If he or she goes, then I’ll inherit,'” Chandra said.

As she nears the last stage of her own life, Chandra said she has been proactive in preparing her will and making sure her family will defend not only her views, but her pro-life values.

“They’re clear on those issues,” she said, although she does not wish her life to be prolonged unnecessarily.

“If there’s no hope for me physically, why not let God intervene whenever he wants to take me?” she asked.