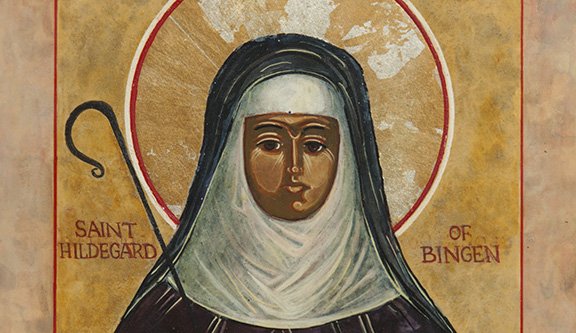

St. Hildegard of Bingen is depicted in an icon by Augustinian Father Richard G. Cannuli. Pope Benedict XVI signed a decree May 10 that formalized her Sept. 17 feast and added her name to the church’s catalogue of saints. The German Benedictine mystic, although venerated for centuries, had never been officially canonized. (CNS photo/courtesy of Father Richard Cannuli) (May 11, 2012) See POPE-SAINTS May 10, 2012.

St. Hildegard of Bingen and St. John of Avila named doctors of the church

by Woodeene Koenig-Bricker

Special to The Leaven

While we think of a doctor as someone who heals the sick, the word actually comes from the Latin word “docere,” meaning “to teach.”

So in the language of the church, a doctor is a saint of “eminent learning” and “great sanctity,” whose writings carry a universal and timeless message for all people.

That’s why when earlier this week Pope Benedict named St. Hildegard of Bingen and St. John of Avila doctors of the universal church, he considered it a moment of considerable importance — and relevance.

The teachings of doctors of the church range from mystical theology to philosophy to defense against heretics, but they all have one thing in common: They help us better understand and live out the Gospel message. Their lessons enable all people to better grasp the great mystery of how God loves and interacts with humanity.

But what makes these two saints particularly relevant to us?

St. John of Avila was a 16th-century Spanish priest, mystic, preacher and scholar. His writing and preaching have influenced many other saints, including St. Teresa of Avila, St. Francis Borgia and St. John of the Cross.

A member of a wealthy family, he studied law, theology and philosophy, eventually being ordained a priest. After his parents’ deaths, he gave his wealth to the poor and devoted his life to the service of the faith. He founded several colleges and was the first rector of the University of Baeza, which became a model for seminaries.

Best known for his guide to the spiritual life and for his “Treaty of God’s Love,” he wanted to become a missionary to Mexico, but instead ended up preaching in areas of Spain that had been under Moorish control and were no longer Catholic.

For us today, John’s example of re-evangelization in an area that had previously been Christian is particularly relevant in light of the new evangelization that Pope Benedict has called for in this Year of Faith.

Most of us will never become missionaries to foreign lands but, like St. John, we can bear witness to the people among whom we find ourselves. St. John’s example reminds us that the ultimate goal for our lives should be to do God’s will.

As he wrote: “Turn yourself round like a piece of clay and say to the Lord: I am clay, and you, Lord, the potter. Make of me what you will.”

The second new doctor, St. Hildegard of Bingen, was a 12th-century German nun, whose popularity has grown both in religious and secular circles in the last several years.

An abbess and founder of several monasteries, she wrote extensively on herbal medicine, created poetry, composed music — including what many consider to be the first opera — and maintained an extensive letter-writing ministry with notables of her time, including popes and St. Bernard of Clairvaux.

She also drew, gardened, painted, and preached. Her widespread activities have made her popular with everyone from feminists, botanists, painters, musicians, and healers, to writers, composers, poets, visionaries, mystics, environmentalists and more.

Because she appeals to so many diverse groups, including many who are not Christian, Hildegard affords an opportunity to find new ways to engage the culture and to proclaim and bear witness to the Christian life, especially in the area of environmental concerns.

While environmentalism as a movement would be a thousand years in the future, Hildegard often wrote about God’s creation, stressing that we are to be stewards, keeping and caring for this world that God loved into existence.

She included the natural world in the “works of God,” a novel approach for her day, but one that resonates with us, saying: “All nature is at the disposal of humankind. We are to work with it. For without we cannot survive.”

Her approach, so strikingly modern, provides yet another opening to introduce the concept of God into our ongoing conversation of conversion with the world at large.

The words of Pope Benedict about these two new doctors remind us that Jesus’ message continues to be relevant for all times: “These two great witnesses of the faith lived in very different historical periods and came from different cultural backgrounds. . . . But the sanctity of life and depth of teaching makes them perpetually present.”

Doctors of the Church

With the addition of John of Avila and Hildegard of Bingen, the church recognizes 35 men and women as doctors of the church. Named in 1298, Sts. Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Pope Gregory I were the original doctors. Other famous doctors include Sts. Thomas Aquinas, Jerome, Francis de Sales and Anthony.

Until 1970, no woman had been named to the ranks, but Pope Paul elevated St. Teresa of Avila and St. Catherine of Siena. Blessed Pope John Paul II named St. Thérèse of Lisieux. St. Hildegard makes the fourth woman doctor.

In order of naming

St. Gregory the Great

St. Ambrose

St. Augustine

St. Jerome

St. John Chrysostom

St. Basil the Great

St. Gregory Nazianzus

St. Athanasius

St. Thomas Aquinas

St. Bonaventure

St. Anselm

St. Isidore of Seville

St. Peter Chrysologus

St. Leo the Great

St. Peter Damian

St. Bernard of Clairvaux

St. Hilary of Poitiers

St. Alphonsus Liguori

St. Francis de Sales

St. Cyril of Alexandria

St. Cyril of Jerusalem

St. John Damascene

St. Bede the Venerable

St. Ephrem

St. Peter Canisius

St. John of the Cross

St. Robert Bellarmine

St. Albert the Great

St. Anthony of Padua and Lisbon

St. Lawrence of Brindisi

St. Teresa of Avila

St. Catherine of Siena

St. Thérèse of Lisieux