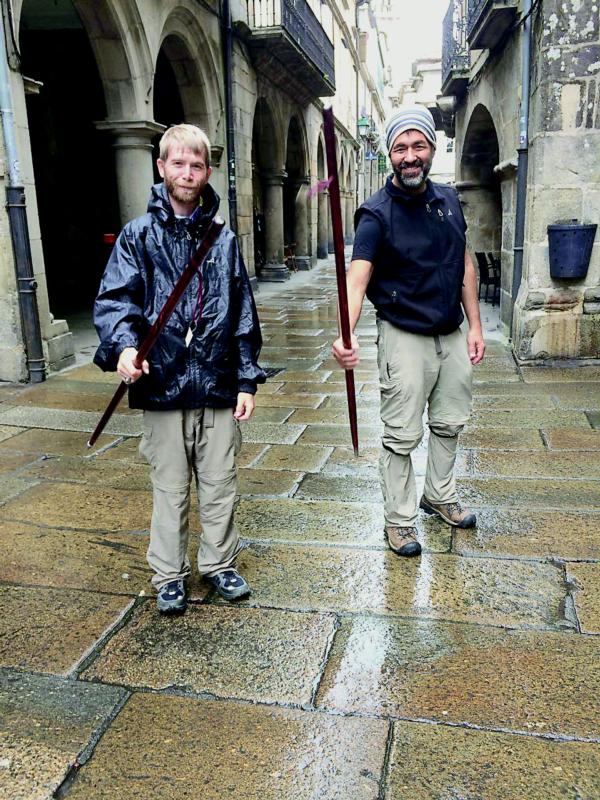

In this undated photo, Luke Hutchins and Mark Peredo raise the walking sticks they bought in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. (CNS photo/Handout via Archdiocese of Indianapolis)

by John Shaughnessy

INDIANAPOLIS (CNS) — Mark Peredo knew he had to do something drastic. His 27-day, 600-mile walking pilgrimage across the Camino in France and Spain in late 2016, left him with a lingering combination of anger and brokenness.

He was also still trying to come to terms with the recent death of his father, who had always been his best friend. And he was still trying to recover emotionally and physically from the horrific accident in 2015 that nearly killed him when another driver struck his car head-on at a high speed — a crash that led Peredo to have eight surgeries.

That’s when Peredo started a search for the driver of the other car, Luke Hutchins.

“After my return from the Camino, I had a need to seek him out, to understand, to see if he was OK,” recalls Peredo, a member of St. Mary Parish in Lanesville in southern Indiana. “There was still this whole forgiveness I was withholding from Luke. I was still angry. I knew I needed another way to go. I was trying to make a forgiveness breakthrough.”

During his search, Peredo found a news report that said the accident wasn’t the result of drugs or alcohol, but an epileptic seizure. For the first time, Peredo realized that Hutchins had suffered, too, and was likely still suffering.

When he finally came face to face with Hutchins in the early part of 2017, Peredo did something that still stuns Hutchins: Peredo asked him if he wanted to walk the Camino with him.

“I was hoping I could create a way to make something great out of something bad — and he would be a partner with me in this,” Peredo told the Criterion, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Indianapolis. “Through nobody’s fault, both of us had almost been killed in the accident. I wanted to do this for myself and him — to walk as brothers, to create something positive for our futures.”

Hutchins had never heard of the Camino, where it was, or what it entailed. But the more Peredo talked, the more Hutchins became swept up in the thought of traveling to a foreign country, of being on an airplane for the first time in his life. Concerns of how the epilepsy might affect him while walking the Camino faded amid the plans of the adventure.

Wanting to help protect Hutchins if he fell on the trail, Peredo bought knee pads, elbow pads and a helmet for Hutchins, insisting he wear them when they began walking.

Finally, in October 2017, they set out from a small town in France on the ancient pilgrimage path that leads to the shrine of St. James at Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. And on the first day for the 49-year-old Peredo and the 33-year-old Hutchins, their journey almost ended in disaster.

“I vomited four times going up the mountain and two times going down the mountain,” recalled Hutchins, who was carrying a backpack that weighed about 40 pounds, similar to Peredo’s. “I felt Mark took care of me. He took my pack. If he wasn’t there, I might have had to stop right there.”

Peredo notes, “He’s throwing up, and he’s throwing up some more. I’m thinking he’s going to die. I take his pack. I’m walking up with his backpack and my backpack.”

Peredo was also carrying some emotional baggage from the journey he had made on the Camino a year earlier due to the death of his father the year before.

But Peredo also remembered the advice that his father sometimes gave him — to “keep going forward” in life. He followed that advice again as he carried the two backpacks.

That approach of moving forward also worked well for Hutchins after that first day.

He stopped smoking within the first few days of the journey, and he began eating lighter meals, relying on more soups and energy drinks that helped with staying hydrated. He and Peredo also stopped by a medical clinic on the Camino where they sought the advice of a doctor about the medicines he was taking for his epilepsy.

“She said if I continued to take all the medicines, I wouldn’t be able to continue the walk,” Hutchins says. “I was taking eight medicines, and I reduced it down to two.”

With all the changes, he felt better, more confident, and on one of the mountains they climbed, he found himself passing other pilgrims. He even stopped to help one of his fellow pilgrims make it up the mountain.

“She gave me a cross from Israel,” he recalls.

There was also the night when he danced with some of his fellow pilgrims, the day when a herd of sheep made him smile as they seemed to come out of nowhere, and the stops in the churches, the cathedrals and the small towns along the way — all part of an adventure that he describes as “a brand new experience into a whole new world.”

Many times on the Camino, Hutchins and Peredo opened their souls to each other. “We talked about each other’s families, our life experiences,” Hutchins says.

At other times, they became frustrated and irritated with each other. On those days, they walked with other pilgrims, keeping their distance from each other.

“There were moments when you wanted to knock each other’s blocks off,” Peredo says. “We’re human beings. We have our trials and our issues that we deal with. We’re not perfect. But what I found on this trip was the peace of walking with him. We became good friends on the trip. My father was my best friend. I consider Luke as closer to a best friend than I’ve had in years.”

Hutchins notes, “I pretty much treat him like my brother.”

The depth of their bond overflowed when they sometimes talked about faith. Peredo considers his Catholic faith as an important part of his life, with “a special place in my heart for Mary.” Hutchins found his faith growing during the pilgrimage.

“We were talking about faith and his future one day,” Peredo recalls. “I was asking him about maybe being a youth pastor. Right then, a rainbow comes out, and church bells are ringing.”

After 40 days and 460 miles of walking, Peredo and Hutchins reached the shrine of St. James. By the end of the journey, Hutchins had long ago discarded his helmet, and he suffered only one seizure along the way.

“It was incredible I was able to walk it,” he says. “Mark kept encouraging me. When we got to Santiago de Compostela, I was so happy. It was finally mission complete. I can finally go home now. I was missing my kids so bad. It was a really great experience. If I had the chance to do it again, I would.”

For Peredo, the second pilgrimage gave him the peace and healing that had eluded him during his first journey along the Camino. He embraced part of that peace and healing with Hutchins in a way he never expected.

“The best parts of walking together for me were being able to joke about stuff,” Peredo says. “By the end of the trip, we were talking about the accident and joking about the accident.”

He pauses, collecting his thoughts about how far he and Hutchins have come from that moment when their worlds collided.

“For me, going through this process of healing and letting go and not hating is something I needed to do — to prove to myself, to prove to my children that you have to stay the course, and that something good will come from it.

“I wanted to go back because I was broken. Luke wanted to do it because he was broken. We helped each other through this.”