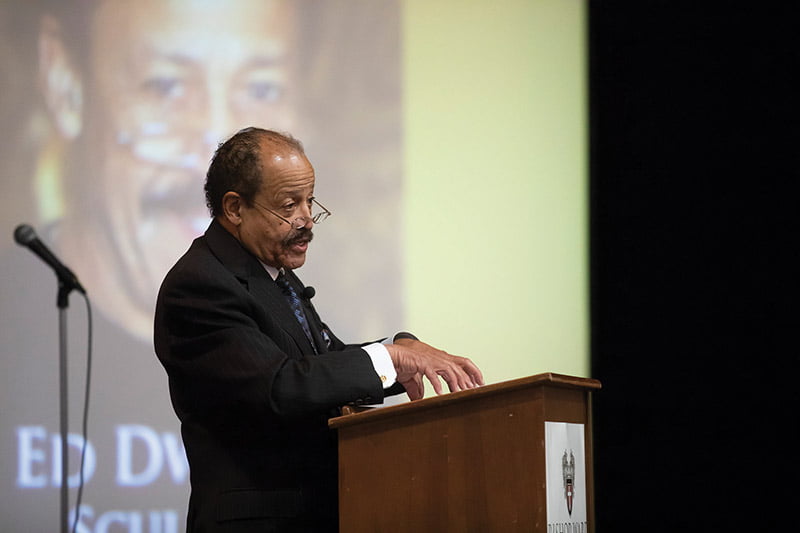

Ed Dwight was the first African American trained as an astronaut. He was also the first African-American male to graduate from Bishop Ward High School in Kansas City, Kansas. Dwight returned to his alma mater on Nov. 7 to talk about his life’s journey. LEAVEN PHOTO BY DOUG HESSE

by Olivia Martin

olivia.martin@theleaven.org

KANSAS CITY, Kan. — They say history is made every day. And for 85-year-old Ed Dwight, making history has defined much of his life.

Though Dwight was the first African-American trained as an astronaut, one of his proudest accomplishments was being the first African American male to graduate from Bishop Ward High School in Kansas City, Kansas.

Dwight graduated in 1951 — three years before the desegregation of schools across the country was ordered by the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

Dwight visited his alma mater on Nov. 7 to address Bishop Ward, as well as Wyandotte County Catholic grade school students in an assembly.

“My sister and I had to go through a lot of stuff to make it through Bishop Ward,” said Dwight. “[But] this school was the best thing that happened to me.”

Dwight’s parents were devout Catholics, and his mother worked for three years to have her children accepted to Bishop Ward.

His admittance there was the start of a new life for Dwight and his family. His younger sister, Sister Martin Mary, even became the first African-American nun with the Sisters of Charity in Leavenworth in 1957.

Although Dwight was permitted to attend Bishop Ward, traces of the mentality of the time remained.

“They said I could not shower with white kids,” said Dwight, “so they had to build me a separate shower.

“I did not let it bother me at all because I had a mission in my head.”

The mission

That mission mentality continued to lead Dwight beyond Bishop Ward and into a degree in aeronautical engineering and later as a pilot in the Air Force.

“Anywhere I went, I was the only black officer,” said Dwight. “It was very fascinating how Bishop Ward came into play.

“In my time [at Bishop Ward] listening and thinking, I learned how white people think.”

Dwight was on a fast track to becoming a general when he received an unexpected invitation.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy wrote 28-year-old Dwight a letter, inviting him to become the first black astronaut trainee.

“I just couldn’t resist it,” said Dwight. “I thought, ‘If I become an astronaut, that would really help my people.’”

Though Dwight never made it to space, he made several high- altitude flights and completed astronaut training.

That included centrifuge training, which is designed to prevent a loss of consciousness due to extreme levels of acceleration one might experience in rocket takeoff and landing.

“They test you to see how many G’s you can take before you black out,” said Dwight.

The force of acceleration is measured in G’s — one G being equivalent to the force of the earth’s gravity upon a body.

“At 15 G’s, your tear ducts close, so the tears come over [the side of your face] and they hit your ear like a bullet,” recalled Dwight.

But after President Kennedy’s assassination and seeing the rising number of deaths among his Air Force comrades, Dwight decided to retire and move into private life.

From astronaut to artist

Dwight began the next phase of his working life in Colorado at IBM. He eventually went on to try a barbecue restaurant and then the construction business.

All the while, the artistic talent he had carried since childhood was begging for an outlet.

“At the construction sites at the end of every day, I would pile all of this metal in the back of my Mercedes-Benz and drive it home,” said Dwight. “On the weekend, I started making art out of it.”

And it was good — so good that Colorado Lt. Gov. George Leslie Brown took notice. Elected in the early 1970s, Brown was the first black to hold the position.

And he insisted Dwight create the sculpture he planned for the Capitol building.

Brown pointed out to Dwight that though African-Americans have been in the United States for 350 years, there were no images of a black person in any city park, museum or public square.

“He told me, ‘You’re going to change that,’” said Dwight. And he did.

At the age of 45, Dwight pursued his childhood dream of becoming an artist and went on to earn his MFA in sculpture from the University of Denver.

Since that time, Dwight has created hundreds of public monuments and sculptures across the country celebrating African-Americans, including the Mother of Africa Chapel at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington; the memorial to Rosa Parks in Grand Rapids, Michigan; the inaugural sculpture of President Barack Obama; and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. memorial in Houston.

And it all comes back to Bishop Ward.

“There is something magic in going here, because people care,” Dwight told his student audience.

“That’s the most important thing you can possibly have at any school,” he added.

The assembly concluded with a student awards ceremony and the announcement of Wyandotte County’s official recognition of Nov. 7 as Ed Dwight Day.

Daniela Gonzalez was the Ed Dwight STEAM award recipient for art.

Gonzalez, a Bishop Ward senior and parishioner of Christ the King Parish in Kansas City, Kansas, plans to join the Navy after graduation, with hopes of one day becoming a pediatrician — hopes that were bolstered after hearing Dwight’s story.

“[He] showed us that even though he was in the lower system during the ’50s,” said Gonzalez, “he still overcame everything — all of the challenges.

“It shows us that anyone can overcome challenges.”