by Moira Cullings

moira.cullings@theleaven.org

ROME — Every evening, the authorities here come on the news to announce “grim” statistics regarding the coronavirus’ impact on Italy, said Paul Haring, senior photographer for Catholic News Service (CNS).

“The last few days have just been devastating for Italy,” he said.

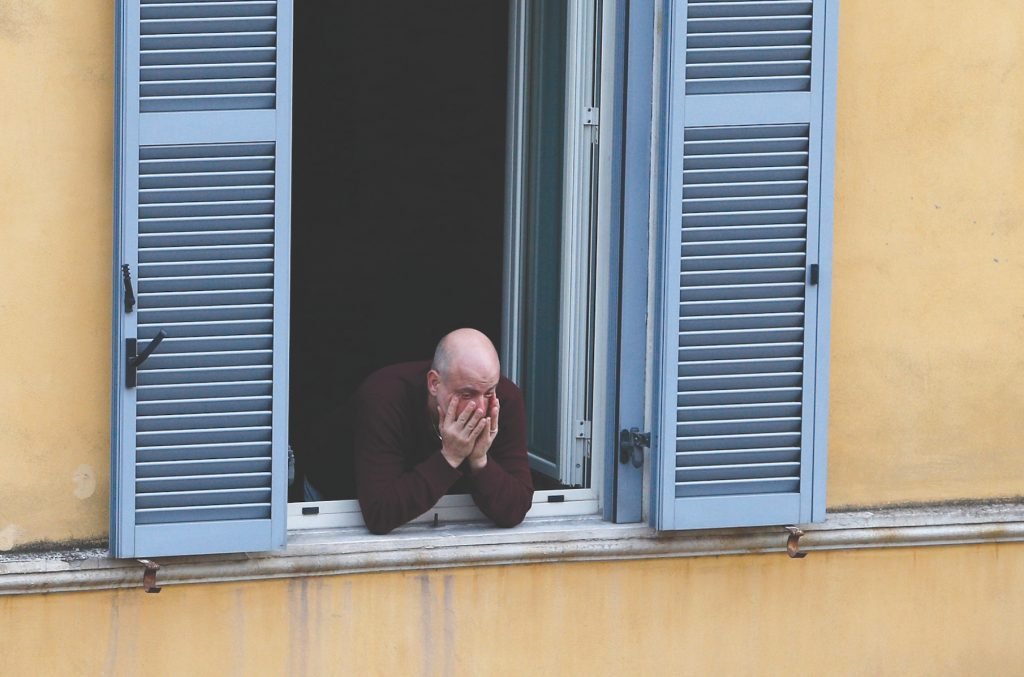

But right after the announcement, citizens in Rome step out onto their balconies to sing together.

“My neighborhood isn’t very good, and the first two songs weren’t very singable,” said Cindy Wooden, Rome Bureau Chief for CNS.

“But tonight, we did OK,” she said with a laugh.

On March 16, The Leaven caught up with Haring and Wooden, who you might remember from a story we wrote about the pair’s book, “Pope Francis: A Guide to God’s Time,” in December 2014.

Haring has lived in Italy for 11 years and Wooden for 30.

Their lives have been turned upside down since the coronavirus outbreak prompted Giuseppe Conte, the prime minister of Italy, to order a lockdown throughout the country.

‘The last week at the Vatican’

Before the coronavirus outbreak, Wooden walked to work at a Vatican-owned building next to the Vatican press office after grabbing a cappuccino from her usual cafe.

Around six staff members met in the morning to divide up responsibilities for the day — from reading Vatican documents to photographing Pope Francis.

Haring was typically out and about taking photos, editing them and ensuring CNS had adequate visual coverage for stories on the Vatican.

“As the crisis hit Italy and the Vatican started taking preventative measures, we had what I call the last week at the Vatican,” he said.

The staff actually began working from home on March 6 because the internet was down at their office.

“But we could still go out anywhere and everything was still open,” said Wooden.

On March 8, Wooden attended Mass and, at that point, the only thing different was that the seating was spread out.

“That was kind of weird to be at Mass with all these people sitting one yard apart from each other,” said Wooden.

Little did she know, but that night, the government would ban all public gatherings, including baptisms, Masses, weddings and funerals.

A couple days later, people were encouraged to stay home. Coffee bars and restaurants were allowed to remain open until the early evening, but that didn’t last long.

“The place where I get my morning cappuccino, they put tape on the floor in these one-meter grids [to help form the line],” said Wooden.

“Italians have a reputation for not knowing how to stand in line,” she explained. “It’s not a stereotype. It’s based on fact.”

While ordering her coffee at a distance, a woman stepped right in front of Wooden.

“It became very clear, very quickly that wasn’t working,” she said. “So that lasted only two days.”

Meanwhile, the Vatican began to shut down, too. But not right away, said Haring.

Pope Francis’ Sunday Angelus prayer was broadcast on television and online, but the pope would still come to the window to overlook St. Peter’s Square.

“There were these compromises early on,” said Haring. “Now at the Vatican, pretty much everything has shut down.”

Life in lockdown

Italian citizens are required by law to remain in their homes unless they need to travel to the grocery store, pharmacy or to pick up a newspaper.

Some exceptions are made for work. But citizens must carry a written declaration explaining where they’re going and why, in case they’re stopped by police, said Wooden. The police will ticket people if they are outside their homes without a good reason.

The restrictions impact almost every move they make, but Haring and Wooden are healthy. And they are safe.

Wooden is single and lives alone in an apartment with a bedroom, dining room, kitchen and living room.

“It’s pretty big by Italian standards for one person,” she said. “But I quickly understood that I needed to create separate zones in the house.

“The living room is where I relax and watch TV. The dining room is where I’m working now. I need to change rooms throughout the day,” she said.

Staying physically healthy has been a challenge, so Wooden finds herself pacing a lot.

“I don’t know what the woman downstairs thinks about that,” she admitted with a laugh.

Haring, on the other hand, is married with children and lives with his family in a two-bedroom apartment.

“I would say one of the challenges is psychological,” he said. “It’s very easy to get wrapped up in the endless coverage that you see all around you in every news site.”

Because part of their work involves tracking local news, “sometimes it’s hard to free your mind from this and from the worries of it,” Haring ex-plained.

“You have this feeling of being in crisis mode, when you know you have your regular work to do as well,” he said.

Although the announced lockdown and closures are officially due to end April 3, the Vatican announced March 15 it would not distribute tickets to the public for any Holy Week or Easter liturgies.

“I was thinking by Easter that we’d be out of this,” said Wooden, “and that we’d really be able to celebrate the Resurrection.

“I guess I’m going to have to rethink how I celebrate the Resurrection.”

Finding light in the darkness

During their time at home, both Haring and Wooden have found goodness and hope.

“I’ve been impressed with how compliant people have been with this order,” said Haring. “Italians are not known for following the rules and they’re not known for lines or having any sense of a line.

“Yet, we see people diligently following [the rules now], waiting in line for the supermarket. They’re letting four people in at a time in some supermarkets, and people are patiently waiting outside.”

The supermarkets in Rome are well-stocked with food and toilet paper. The only product missing, said Wooden, is hand sanitizer.

“People have a sense [that] we’re in this together,” said Haring.

For Wooden, singing together with her neighbors or chatting with them during the day has been a light in the darkness.

“It’s people I’ve never met before,” she said. “I’ve seen them around, but we’ve never [talked].

“The guy across the street the other day said we should introduce ourselves. I said, ‘Yeah, I’m Cindy.’ He told me his name.”

Haring and his family have prayed together more.

“It really calls you to lean on your faith,” he said. “You don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Although the lockdown “is a major challenge for the country and its people,” Haring sees how critical it is to hinder further damage from the coronavirus.

“Without the lockdown, we would be in a very dangerous situation here in Rome,” he said.