by Justin McLellan, Catholic News Service

VATICAN CITY (CNS) — More than 2 billion people in over 50 countries were set to go to the polls in 2024, according to the Center for American Progress, but Pope Francis has said he is worried that people are more disconnected than ever from the governments that are meant to provide for their well-being.

Participating in a conference in Trieste, Italy, July 7, the pope discussed democracy at length. In preparation for that visit, the Vatican publishing house produced a booklet compiling papal speeches on democracy and featuring a new introduction to the text written by Pope Francis.

The booklet was published in Italian July 7 as an insert in Trieste’s local newspaper, Il Piccolo.

In it, the pope wrote that while democracy has spread globally in recent decades, today it “seems to be suffering the consequences of a dangerous disease,” that of “democratic skepticism.”

People’s distrust in democracy, which “sometimes seems to yield to the allure of populism,” he wrote, ultimately stems from its perceived difficulty in addressing current challenges, such as, “issues related to unemployment or the overwhelming technocratic paradigm.”

In his speech at the event July 7 during Italian Catholic Social Week, the pope underlined the need to train people in democratic participation from a young age and instill them with “a critical sense regarding ideological and populist temptations.”

The four-day conference, organized every three to four years by the Italian bishops’ conference to engage Catholics in social issues, chose as the theme for its 50th edition “At the Heart of Democracy.”

True democracy, he added, does not entail merely voting, but creating the conditions and space for “everyone to express themselves and participate” in society.

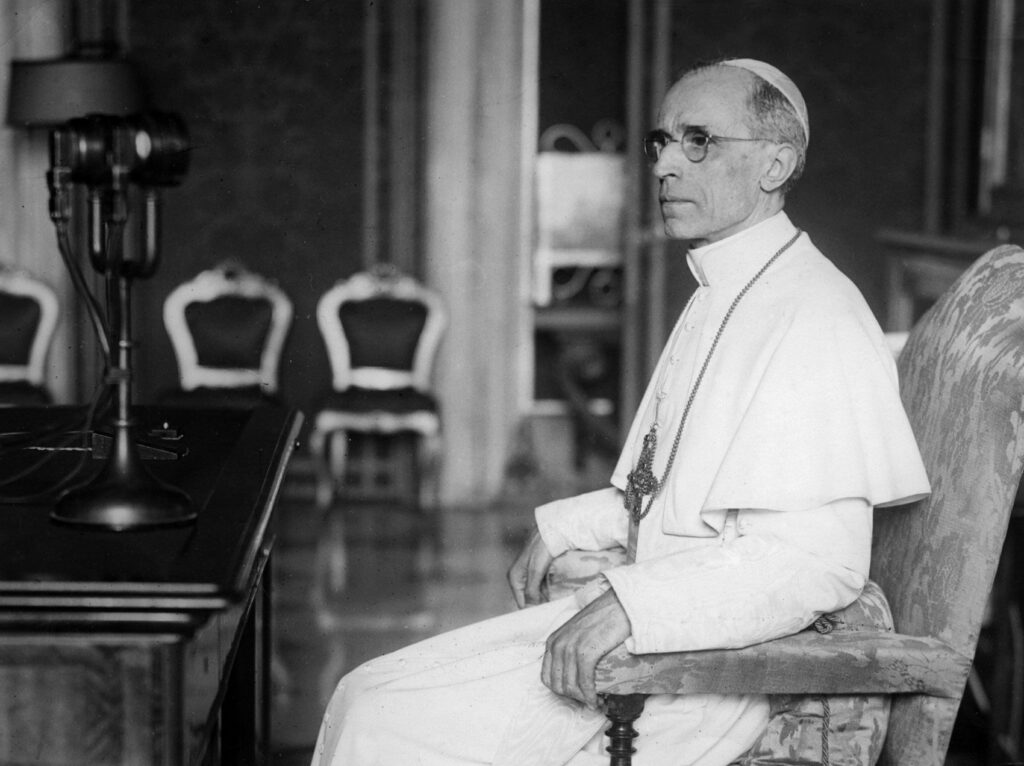

That sentiment echoes a distinction made by Pope Pius XII in his radio message to the world Dec. 24, 1944. Still in the midst of World War II, the pope discussed the key difference that exists in a democratic system between “the people” and “the masses.”

A people, the pope said, “lives and moves by its own life energy” and is composed of individuals “conscious of (their) own responsibility and (their) own views.”

“The masses, on the contrary, wait for the impulse from outside, an easy plaything in the hands of anyone who exploits their instincts and impressions; ready to follow in turn, today this flag, tomorrow another,” he noted.

Whereas a people actively involved in democracy instills into a population “the consciousness of their own responsibility” and “the true instinct for the common good,” Pope Pius issued a stark prediction for the fate of the disengaged masses: “in the ambitious hands of one or of several who have been artificially brought together for selfish aims, the state itself, with the support of the masses, reduced to the minimum status of a mere machine, can impose its whims on the better part of the real people.”

As a result, “the common interest remains seriously, and for a long time, injured by this process, and the injury is very often hard to heal,” Pope Pius said.

For Pope Francis, to counter the tendency to drift toward merely becoming “the masses” entails developing a sense of solidarity and togetherness, from which grows a will to participate in public life.

In authoritarian regimes, “no one participates; everyone watches passively,” he wrote in his introduction to the booklet. “Democracy, on the other hand, demands participation, demands putting in one’s own effort, risking confrontation, bringing one’s own ideals, one’s own reasons, into the question.”

He added that “standing at the window, watching idly what is happening around us, is not only ethically unacceptable but also, even from a selfish perspective, neither wise nor convenient.”

Or, put more succinctly, “indifference is a cancer of democracy,” Pope Francis said during his July 7 speech.

Yet in his text the pope wrote that it is by leveraging democracy’s greatest asset that society can overcome its sense of passivity.

“Democracy has in it a great and unquestionable value: that of being ‘together,'” he wrote, praising the model for exercising government power “within the framework of a community that freely and secularly confronts each other in the art of the common good.”

Togetherness, the pope added, fosters a “positive and almost concrete sense of solidarity, which comes from sharing and advancing, for example in the public arena, issues on which to find convergence.”

The pope highlighted several pressing issues in society which require joint action and which people are called “to engage democratically”: receiving migrants, falling fertility rates and the pursuit of peace through negotiation rather than increased firepower.

Particularly “in these times overshadowed by war,” the pope prayed for a “more convinced commitment to a fully participatory democratic life aimed at the true common good.”