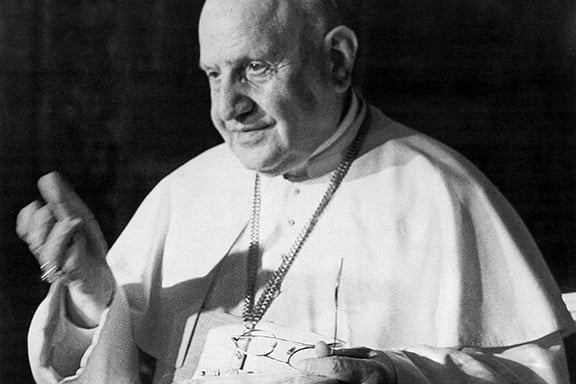

Pope John XXIII is pictured in this undated photo. Oct. 11 will mark the 50th anniversary of the first session of the Second Vatican Council, which was called by Pope John XXIII. (CNS photo/courtesy of Archbishop Loris Capovilla) (May 4, 2012) See VATICAN LETTER May 4, 2012.

Despite differences, John XXIII and Paul VI both guided council

by Joe Bollig

joe@theleaven.org

KANSAS CITY, Kan. — The pope was dead. The 19-year pontificate of Pope Pius XII ended on Oct. 9, 1958.

He would be solemnly buried and a new pope would be solemnly elected. The church would continue, of course.

It was as simple as that — and yet, not so simple.

The future of the church, the direction it would go, depended a great deal on the kind of man the cardinals — with the Holy Spirit’s guidance — chose from among themselves.

One man preparing to go to Rome for the funeral and the following conclave was the Patriarch of Venice, Cardinal Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli.

Some people thought or hoped he would be pope. Not Cardinal Roncalli, though, according to the author Vittrorio Gorresio.

As he packed for the trip, Cardinal Roncalli mused to a friend that Pope Pius X once lived in that very apartment. His predecessor had every intention of returning to Venice after the conclave of 1903 and had bought a round-trip ticket.

“Will you buy a one-way ticket?” the friend asked hopefully.

“Hush, be quiet — God save me from such a misfortune!” replied Cardinal Roncalli.

“We’re told that when the cardinals came together to elect a successor to Pope Pius XII, they were having some difficulty coming to a consensus,” said Sister Maureen Sullivan, OP, an assistant professor of theology at St. Anselm College in Manchester, N.H.

“And so they ultimately agreed on Cardinal Angelo Roncalli,” she said. “They viewed him very much as an interim pope, a placeholder. They didn’t expect anything gargantuan to come from him.”

This “safe” choice, the 77-year-old Pope John XXIII, would in fact shake up the church by launching the Second Vatican Council.

He had real warmth, deep authenticity, and the ability to connect with people. In time, the people gave him an unofficial title: Good Pope John.

Pope John XXIII came from a large, humble and devout family that lived in a village in the Lombardy region of Italy. His parents were poor sharecroppers.

“Italians come to ruin most generally in three ways: women, gambling and farming,” he once said. “My family chose the slowest one.”

He was ordained a priest in 1904 and slowly rose through the diocesan bureaucracy until he was drafted into World War I.

After the war, he returned to diocesan ministry until he was tapped to become part of the Holy See’s diplomatic service. He served the church in non-Catholic countries: Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey.

“He was getting a broadening education that many in the insider circles of Rome were not getting, just by virtue of his ministry,” said Sister Maureen. “He was really having to stretch from this very closed world to interfaith conversations.”

On the night the Second Vatican Council opened, Oct. 11, 1962, he came out on his balcony and spoke to the crowd.

“When you head home, find your children,” he said. “Hug and kiss your children and tell them: ‘This is the hug and kiss of the pope.’”

“There was this real gentility and holiness about this man,” said Sister Maureen. [He also said,] ‘I am the pope because God wanted me to be pope, but I am first and foremost your brother.’”

Kind and gentle he may have been. But John was no pushover. Many cardinals opposed his council, but he wouldn’t let it be derailed, as Gorresio wrote in his book, “The New Mission of Pope John XXIII.”

“They are certainly zealous men, but it is not they who are ruling the church,” Pope John XXIII said. “That post is mine, and I do not wish anyone to hobble the progress toward a council.”

Pope John XXIII encouraged freedom of thought and openness for theologians, members of the curia, and more forward-thinking bishops.

But he didn’t lay out a detailed agenda.

“There was real confusion on the part of bishops who would be in attendance,” said Sister Maureen. “[It was], ‘What exactly does the pope want us to do?’”

Pope John XXIII asked the bishops what they wanted. When they arrived in Rome, amazing things began to happen. Bishops from all over the world got to know each other and compare notes.

Only one thing could stop Pope John XXIII. In 1962, he was diagnosed with cancer and died on June 3, 1963. Some thought the council would die with him.

But it didn’t. “Good Pope John” was succeeded by Cardinal Giovanni Montini of Milan. He took the name of Pope Paul VI.

The two popes could not have been more different. While Pope John XXIII was portly, gregarious and outgoing, Pope Paul VI was thin, serious and somewhat shy. He was from aristocratic stock, a well-off family.

But there were some similarities. Pope Paul VI also served in the Holy See’s diplomatic service. While in Milan, he was known as “the archbishop of the workers,” wrote Peter Hebblethwaite in “Paul VI: The First Modern Pope.”

Pope Paul VI believed in Pope John XXIII’s work. His role at the council had been muted, but he gave his enthusiastic support, according to Hebblethwaite. When he became pope, he immediately said he’d continue the council.

In some ways his job was harder than his predecessor’s, said Sister Maureen. Factions developed at the council, and Pope Paul VI had to work skillfully to prevent a schism. Some called him “the Hamlet Pope” for his supposed indecisiveness.

“He really could see both sides of the story and not only see them, but the implications down the road,” said Sister Maureen. “I think [‘Hamlet Pope’] is an unfair title. Maybe he thought too much about it, or the consequences that could follow. I think he agonized where the church would go in the future.”

From the close of the council until his death on Aug. 6, 1978, Pope Paul VI worked doggedly to implement the council and hold the church together, all the while suffering criticisms of those who thought the council went too far and those who thought it didn’t go far enough. Indeed, it caused him to suffer.

“Certainly he was not happy with everything that happened after the council — who could have been?” said Father Joseph A. Komonchak, the English-language editor of “The History of Vatican II,” in a Catholic News Service story.

“I think that he was very distressed by the signs of a kind of a rebellion and even revolution,” continued Father Komonchak. “But I think he did a good job.”

Pope Paul VI’s confessor, Father Paolo Dezza, SJ, offered greater praise: If Pope Paul VI wasn’t a saint when he was elected pope, he became one.