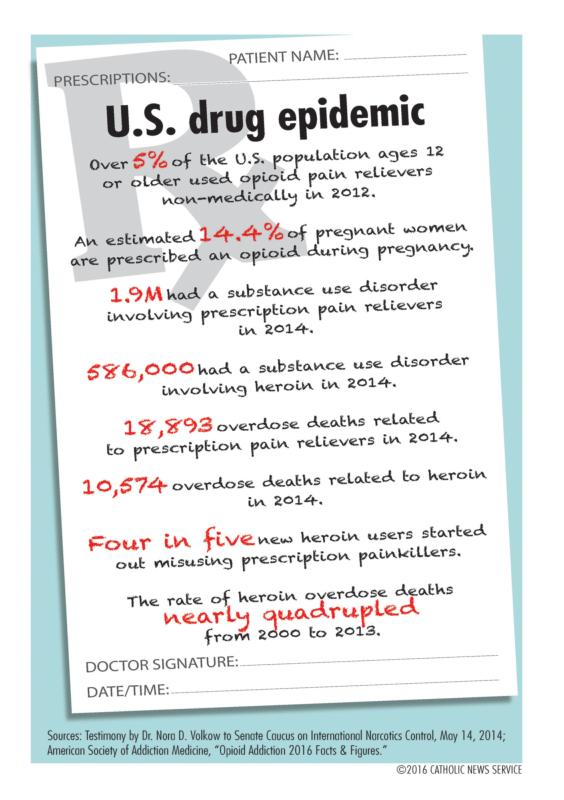

Federal and local governments and social service agencies are scrambling to curb the explosion in U.S. opiate use. (CNS graphic/Liz Agbey)

by Mark Pattison

WASHINGTON (CNS) — “Religion is the opiate of the masses,” German philosopher Karl Marx is famously credited with writing in the 19th century. If it ever was true, it’s not anymore. In the United States today, opiates themselves are the opiates of the masses.

It used to be that heroin was the opiate for society to reckon with. Now, however, prescription opiates are making the problem worse. The demand for prescription opiates such as OxyContin — long labeled “hillbilly heroin” for its use in rural areas — and Vicodin have led to the kind of drugstore robberies and break-ins that had been common more than a generation ago. Forged prescription slips, criminal rings to sell these drugs on the street, and skyrocketing overdose and death rates have prompted federal action.

On March 29 in Atlanta, home to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, President Barack Obama unveiled a strategy to combat the use and abuse of opiates, including the prescription version, often referred to as opioids.

Some elements of the multipronged effort include expanding access to treatment; setting up a task force on establishing parity between mental health and substance use disorders, then implementing that parity within the Medicaid system; preventing opioid overdose deaths; expanding partnerships between public health and public safety agencies to stem the spread of heroin; investing in community policing to combat heroin’s spread; and tackling substance use disorders in rural America.

In February, Obama, in his budget proposal to Congress, sought $1.1 billion in new funding to help every American with an opioid use disorder who wants treatment get the help they need. The key phrase is “want treatment.”

“We have kids who are 12 or 14. They use heroin,” said Lydia Porter of Catholic Charities of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who helps oversee Evergreen House in the capital city, where up to 23 women can receive treatment and counseling at a time. More disturbing, though, is that Evergreen House is now seeing “heroin addicts that are coming in at 30, coming in for the first time, coming in using opiate pills that they got from a doctor.” The body builds up a tolerance to the prescription drug, and the women seek out stronger stuff to kill the pain, feel the high — or both.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine subdivides age groups for all kinds of substance abuse, but has a catch-all category for ages 26 and up. This new, older addict is a growing phenomenon, according to Porter. “At 30, you have much more to lose because you have not been a drug addict. You have a house, kids, a family, a car, degrees, the things that make up a good life according to society’s standards. You can lose all these things before you get desperate,” she told Catholic News Service. By comparison, women in their 20s with a longer history of addiction are “much more willing to never live that way again,” Porter added.

The spread of opiate use in the United States is, ironically, sobering.

ASAM’s “Opioid Addiction 2016 Facts & Figures” reported that four in five new heroin users started out misusing prescription painkillers. “As a consequence, the rate of heroin overdose deaths nearly quadrupled from 2000 to 2013,” it said. But that number is eclipsed by prescription opioid deaths: 18,893 related to prescription pain relievers in 2014 compared to 10,574 overdose deaths from heroin. When it comes to dependency, the ratio is even more skewed: “1.9 million had a substance use disorder involving prescription pain relievers and 586,000 had a substance use disorder involving heroin,” the report said.

In testimony delivered in 2014 by Dr. Nora D. Volkow to Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, “there was a fivefold increase in treatment admissions for prescription pain relievers between 2001 and 2011,” she said. In 2012, more than 5 percent of the U.S. population aged 12 years or older had used opioid pain relievers non-medically, and more than one in seven pregnant women are prescribed an opioid during their pregnancy.

Dr. Jeffrey Berger, medical director of Guest House, a well-known recovery facility for priests located in the Detroit suburb of Lake Orion, Michigan, said that while the majority of priests in treatment struggle with alcoholism, some have come in with opioid addictions. Berger, prior to working for Guest House, had 30 years of experience with opiate abuse at Brighton Hospital about an hour outside Detroit. Guest House focuses on abstinence-based treatment, which Berger wholly supports.

Berger said he was buoyed by Pope Francis’ remarks in 2014 to the International Drug Enforcement Conference, meeting in Rome. “The problem of drug use is not solved with drugs,” the pope said. “To think that harm can be reduced by permitting drug addicts to use narcotics in no way resolves the problem. … Substitute drugs are not an adequate therapy but rather a veiled means of surrendering to the phenomenon.”

The current wave of abuse began in the 1980s, “when there was a big push to treat pain,” Berger said. The medical community, he added, seemed then to move away from what had been its “prevailing medical philosophy” to “use as little of an opiate drug as you can, and for as short a time period as possible. The danger of addiction with these drugs was high.”

Berger lauded one component of the federal effort. “One of the directions they’ve gone, which I heartily approve of, is they’ve made it harder to prescribe Vicodin,” which he pegs at six times the strength of codeine, which had been typically prescribed in the past. Now, patients must visit their doctor to get a fresh prescription rather than allowing the physician to call in a refill to a pharmacy. The state of New York is going one better by eliminating paper prescription tablets and moving to an automated system, in part to root out drug abuse.

Nobody is saying the scourge of opiate addiction will be wiped clean anytime soon. But Catholic Charities’ Porter told of one woman’s journey. “She had a rough life. When she was an orphan, she was abused sexually — multiple rapes, lost babies, physical abuse. God knows what her biological parents are, maybe they were drug addicts. She took to the streets early. She was set up for a long history of drug addiction.

“She went into treatment very young, and that’s it. Right now she’s had over 30 years drug and alcohol free,” Porter said. The kicker: This woman now works alongside Porter to help treat today’s addicts.