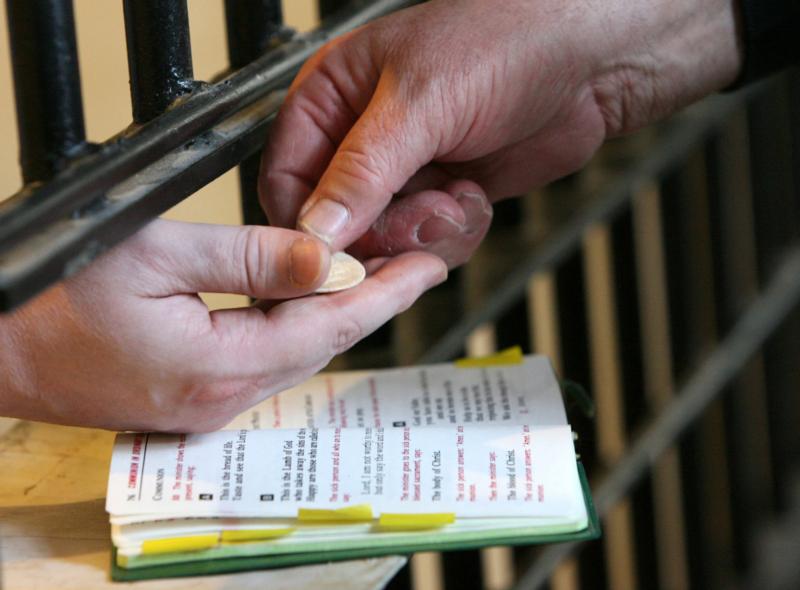

A deacon distributes Communion to a death-row inmate in 2007 at Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Ind. Pope Francis will visit the Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility in Philadelphia in September as part of his U.S. visit. (CNS photo/Karen Callaway, Northwest Indiana Catholic)

by Mark Pattison

WASHINGTON (CNS) — When Pope Francis makes a stop at the Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility in Philadelphia in September as part of his U.S. visit, it may seem like part of the pope’s usual routine.

His visits to prisons as part of his pastoral journeys to other countries has become part and parcel of the pope’s style, just as it had been for St. John Paul II to visit pockets of the Polish diaspora during his well-traveled pontificate.

But visiting fellow countrymen once removed is one thing. Visiting criminals and crime suspects is quite another.

Although visiting the prisoner was mentioned in one of Jesus’ parables, only a very hardy few — ordained and laity alike — do so.

What they see week in and week out — and what Pope Francis may see during his jail visit — is, in many respects, a beaten-down population hopeful for a better future should they be released, but often without the tools to secure that better future.

“It’s all the petty drugs and too many DUIs and too much stupid stuff,” said Kathleen Barrere, who is part of the jail chaplaincy at Marsh Creek, a minimum-security facility in Contra Costa County, California, in the Diocese of Oakland, for about 100 prisoners who have been sentenced to terms of a year or less for misdemeanor offenses.

Barrere disabuses anyone of the notion that Catholics are somehow more immune than the rest of the population from committing criminal offenses. “There are many, many Catholic people who find themselves in jail,” she said.

Mass is the only Sunday religious activity. Sometimes it draws a couple, sometimes up to 20.

The prisoners’ situation “just grabs you,” Barrere, 64, told Catholic News Service. “You want to save ’em . . . . It’s somebody’s baby boy. I have three children of my own. Stuff happens and you want to reach out to that person … who made a mistake, and maybe you can touch their lives.”

She added that she has never felt unsafe in all the time she has been going to Marsh Creek. “You feel the vibes one way or the other. I never had any of the kind of the creepy feeling that ‘oh, I don’t want to hug this one, he’ll get the wrong idea,'” she told CNS.

Not that hugging is common. After the 9/11 terror attacks, jail officials nixed the holding of hands at the Our Father during Mass, as well as clasping hands at the sign of peace.

But inmates, once released, are welcome at Barrere’s parish, St. Bonaventure in Concord, California. A few have shown up after having served their sentences. But when they’re behind bars, she added, she tells them, “We consider you parishioners while you’re here.”

Father Michael Bryant has been involved in jail ministry in the District of Columbia for the past 35 years, but on a part-time basis since he turned 65 10 years ago.

With a background in psychology and counseling, Father Bryant has ministered to inmates in a 1,365-bed men’s jail. At one time, the population bulged to 2,200 because of overcrowding but it has dwindled this year to its current 1,000, as police, mindful of the district’s new marijuana legalization law, are not arresting people for possession as once they did.

The typical jail resident, awaiting trial on whatever charges have been brought against them, are “on the lowest end of the socioeconomic sector, and they’re people of color,” Father Bryant told CNS. “There’s not too many upper-middle-class here,” he remarked, although he recalls seeing both soon-to-be-paroled spy Jonathan Pollard and his wife were both were in the jail awaiting trial.

“Blacks and a growing number of Hispanics are in these institutions,” he added. “I think it’s this way across the United States. Blacks make up only 12 percent of the population; they make up 48 percent of all the incarcerated.”

The jail sees its share of repeat long-term visitors. “I see them come back over and over again into this facility. They know me and I know them. They can call me by name. That’s just a reality of life,” he noted. “There’s not much of a support system when people come back into the community” following their release. Drug and alcohol abuse, he added, don’t help matters.

Father Bryant established a “Welcome Home” program for communities receiving released prisoners. Now run by Catholic Charities in the Archdiocese of Washington, it seeks “mature people of faith who are willing to ‘walk with’ those returning home from prison. Training prepares compassionate mentors to support returning citizens by offering moral support and practical guidance,” said a brochure describing the program.

There are numerous job-training, educational and life-skills programs available in the Washington area. “We can help them,” Father Bryant said. The programs are free, he added, “but they wouldn’t have a clue as to how to get them.”

Father J. Francis Frazer, a Pittsburgh diocesan priest and chaplain at Pennsylvania state prison in Greene County, notes the prison has the state’s highest population of death-row inmates, about 150. Of the prisoners, about 40 have asked to go to the weekly Mass. Most go; about a dozen cannot, because they are confined to their cells. Father Frazer has to go to them to give them Communion, and won a battle with prison officials to open the cell doors so he can give the Eucharist directly to the men, rather than having to put his hand and the host between the bars of the cell door.

“It was a matter of dignity for them,” Father Frazer told CNS. “It should be more of a personal encounter.”

Even outside Mass, Father Frazer will visit with prisoners. Some are happy to get a Bible or some religious literature,” he said.

“Some of them will just have a religious question. One of them, I think I’ve come a long way with, when I first went to see him, he thought there was no way God could forgive him for what he did. He’s on death row. He murdered people.” The man had been jailed for killing someone — although the conviction was for an offense less than first-degree murder — was paroled, and then killed another person. “He felt God could not forgive him for that. We had a lot of talks with him on that.”

Now, Father Frazer added, “he receives Communion regularly.”

The priest speculated about what Pope Francis might, and might not, see, in his Philadelphia jail visit.

“He probably will not see the everyday running of a prison. He’ll probably see so many people that they pick (in advance). I don’t’ think Francis will probably get into a place like we call ‘the hole.’ But he might! He might push that issue,” Father Frazer said, chuckling, “but I probably don’t think he will. He’ll probably do a walk-through, and I don’t think he’ll get to see too many directly that they could actually sit down with him.”