by Therese Horvat

Special to The Leaven

BASEHOR — From conspiracy theories to quarantines and from symptoms to treatments, both parallels and differences exist between the Black Death that scourged the Middle Ages and today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

At its most virulent stage over four to six years in the late 1340s and early 1350s, the Black Death or Plague — also known as the Great Pestilence — claimed 25 million or more lives in Europe. This plague first adversely affected populations of North Africa and Asia where it originated. It then recurred in subsequent waves over 500 years, causing an estimated total of 75 to 100 million deaths.

As of this writing and by comparison with the Black Death, COVID-19 has resulted in more than two million deaths worldwide in a year’s time.

“There’s a shared humanity that spans centuries,” said John D. Hosler, Ph.D., European historian and member of Holy Angels Parish, Basehor. “We experience things differently, but in many ways the same.”

Hosler’s areas of expertise include medieval warfare, the Crusades and military history. He is a professor of military history at the Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth; the author of several books; and president of the international De Re Militari: the Society for Medieval Military History.

While there are those today who consider COVID-19 a hoax, Hosler notes that wasn’t the case with the Black Death in the Middle Ages. People were literally dying in the streets and were buried in mass graves.

Understanding sources, symptoms

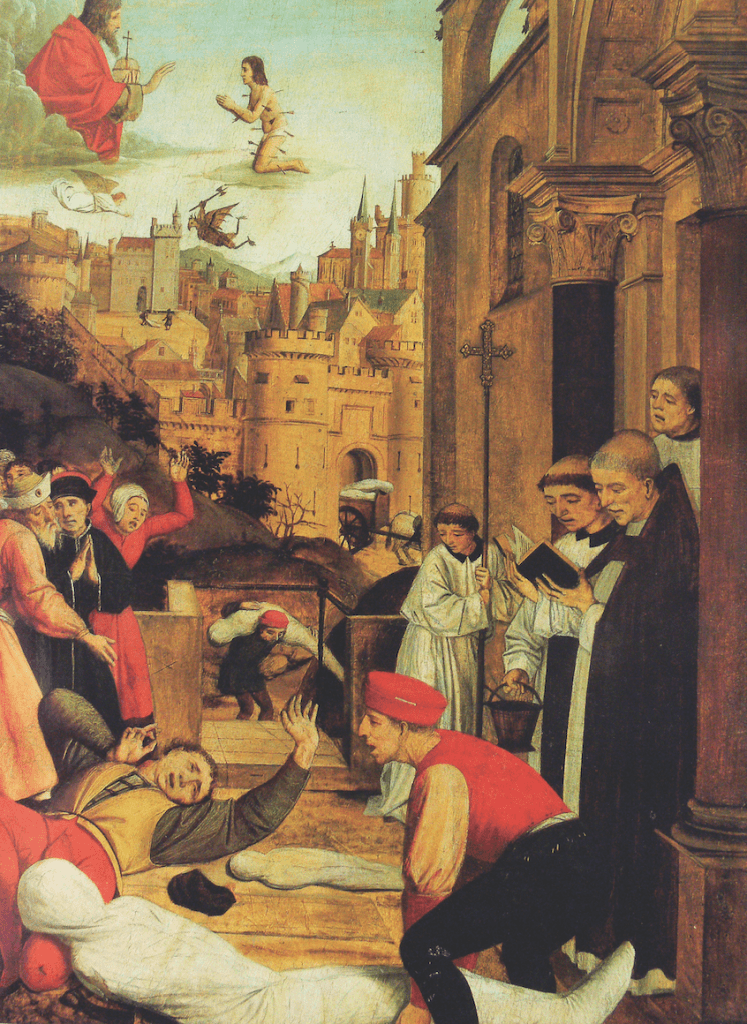

Theories evolved, of course, in an attempt to understand the great unknown cause of the many and rapid deaths. Some turned to the divine, thinking that God was visiting the plague upon people because of their sins. As a penitential rite, flagellants wandered through the streets, flogging themselves.

Others sought to find a scapegoat for the plague. Even though banned from using local wells, the theory arose that because they weren’t drinking the water, the Jews must have poisoned the wells. This and other anti-Semitic sentiments led to the persecution and deaths of many Jewish people.

From the vantage points of history and DNA studies, scientists trace the Black Death to the bacterium Yersinia pestis, transmitted by fleas that had bitten infected rats and then bitten humans. Merchant ships carrying grain and following trade routes likely transported the disease from one continent to another.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 is a new disease caused by a novel (new) coronavirus first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. While bats are the source of other types of coronavirus, the CDC indicates that the exact source of COVID-19 has not been identified. The new virus likely emerged from an animal or bat.

Just as variations of COVID are developing today, the medieval plague manifested in different forms, Hosler explained. The bubonic form was the most common and resulted from flea bites. Its symptoms included fever, headaches, aching joints, malaise, vomiting and the appearance of buboes — swellings that appeared near lymph nodes, turned black and left victims with dark skin splotches. Scholars attribute the name “Black Death” to this discoloration and also to the fact that these were dark times in history.

The pneumonic plague of the medieval ages bore more similarity to COVID, attacking the lungs. Coughs and airborne droplets spread this advanced type of the plague, leading to severe respiratory problems. The more infectious pneumonic form had a higher mortality rate than the bubonic, but both were extremely deadly.

Without the benefits of modern medicine and technology, physicians and quacks alike tried different treatments to stem the spread and outcomes of this killer disease. These included: bloodletting, lancing the buboes and natural remedies.

The latter ranged from ingesting snakeskin to drinking and/or applying concoctions made from items such as eggshells, marigolds and warm beer. Experiencing the plague spreading like a noxious vapor, people resorted to breathing in the fragrance of rose petals or scented herbs to ward off the disease.

Hosler notes that the practices of quarantining and social distancing developed as preventive measures during the Black Death. He cites 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio, who in his introduction to “The Decameron” discusses ways people were dealing with the reality of the plague. Among fearful and fanciful approaches, he describes asceticism; limiting contact and living modestly; adopting a carefree, casual attitude; and fleeing to the countryside.

Social distancing, the wearing of masks, isolation and frequent hand-washing have remained critical measures recommended by the CDC to avoid contracting and spreading COVID-19. Additionally, modern pharmacology has developed vaccines now being administered for long-term immunity to this coronavirus.

The more things change . . .

COVID and the Black Death share commonalities among their victims as well. While the coronavirus has not discriminated based on social status or means, it has disproportionately affected people of color in the United States.

In the Middle Ages, the Black Death likewise cut across social strata. However, Hosler points out that the plague eviscerated the peasant population, many of whom were farmers.

“This eradicated a skill set for agriculture that the nobles lacked and resulted in crop shortages and famine,” he explained. “At a point in time, it may have been difficult to know who was dying from what cause — starvation or the plague.”

In terms of church ministry during the Black Death, Hosler believes that fear and common sense curtailed administration of the sacraments and worship. Plus, priests, monks and nuns were among those dying from the plague. Boccaccio writes that proper Christian burials were placed on hold as has occurred at times during today’s pandemic.

Citing another parallel between the Black Death and COVID-19, Hosler said that even with everyone’s best efforts to curb the spread of the diseases, they spread anyway. He paraphrases Boccaccio, who writes that despite human wisdom and precautionary measures, the Black Death showed up.

That same level of frustration exists today with COVID.

“In spite of lockdowns, masks and other actions,” observed Hosler, “numbers have been off the charts and infection rates increasing.”

Another factor that lingers across centuries is the matter of the human capacity to find balance between living life fully and being safe.

“People in the 14th century were trying to survive,” he concluded. “We’re still dealing with the tensions between staying safe and living our lives as we are used to doing.”