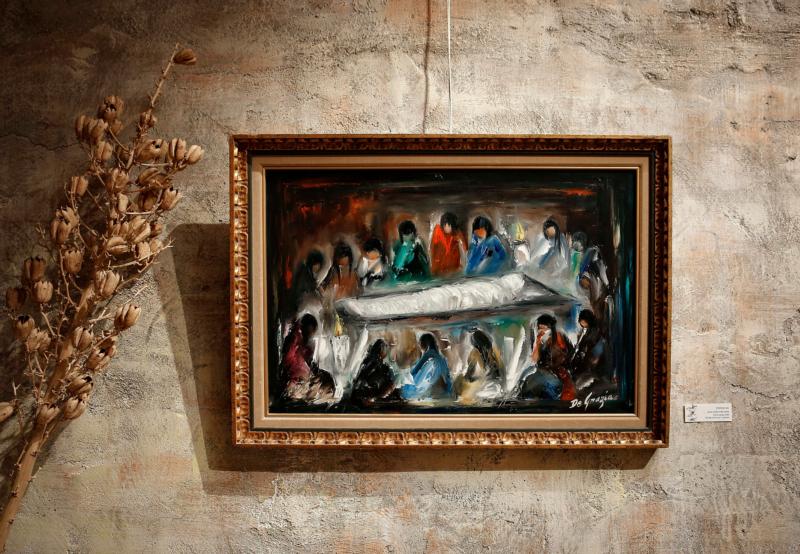

The 14th station — Jesus is laid in the tomb — is seen on exhibit at the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun in Tucson, Arizona, Feb. 12. Arizona artist Ted DeGrazia painted the series in 1964 for the Newman Center at the University of Arizona. (CNS photo/Nancy Wiechec)

by Nancy Wiechec

TUCSON, Ariz. (CNS) — Arizona Artist Ted DeGrazia left behind a huge body of work, with religious and spiritual paintings that have been inspiring people for decades. Yet he was not a churchgoing man and thought he was not holy enough to paint for the church.

“His artwork has its own unique style,” said George Maki, who was visiting DeGrazia’s gallery in the foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains for the first time.

Maki, and his son, Chris, both of Durango, Colorado, sat in the room with the DeGrazia Way of the Cross series for half an hour.

“I think they are wonderful,” the elder Maki said of the paintings. “They are very emotional, very intense, moving . . . a young lady that was in here was actually crying.”

DeGrazia died in 1982. Among his tens of thousands of surviving works are the Way of the Cross; multiple depictions of Our Lady of Guadalupe; a series on Jesuit Father Eusebio Kino, a missionary to the Southwest; and a mission, which the artist designed, built and dedicated to Father Kino.

“I don’t know how many religious paintings he did, but he did a pretty good share,” said Lance Laber, executive director of the DeGrazia Foundation, the organization DeGrazia founded to preserve his art.

According to Laber, DeGrazia’s Catholic heritage, the faith and spirituality of the Indians he befriended and his admiration of Father Kino were inspirations for his religious works.

“DeGrazia never considered himself a churchgoing man,” said Laber. “The mission [he built] is dedicated to Father Kino in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe. . . . He could say what he wanted about not really being religious, but he certainly was.”

A priest approached DeGrazia about painting the Stations of the Cross for the St. Thomas More Catholic Newman Center at the University of Arizona.

Laber said DeGrazia at first refused the job. “He thought he was not holy enough to do that.”

But he had a change of heart and fulfilled the request in 1964.

DeGrazia focused heavily on the project, according to journalists James W. and Marilyn D. Johnson, authors of the 2014 biography “De Grazia: The Man and the Myths.”

“He slept little and didn’t smoke or drink until the entire series had been completed,” they wrote. “He called it a ‘deep religious experience. It was simple, yet exciting — a work on the sensual unity of mankind.'”

Laber said the paintings hung in the Newman Center for a couple of years but were removed and brought back to the DeGrazia gallery because of security and insurance concerns. The artist’s work had been increasing in value. Prints of the series still line the walls of the university’s chapel.

In a recorded statement that accompanies the paintings, DeGrazia said the story of Christ’s crucifixion was “very close to me because I was born Catholic. I was brought up with the Way of the Cross.”

DeGrazia said he painted Christ alternately as black, red, yellow and white “because Christ is in the image of the beholder,” in the image of all people.

He used bold, bright colors as well as muted ones. Yellow, he said, for light, hope and strength; blue for hope and tenderness; red for intensity and suffering. In the landscape of the paintings he incorporated saguaros that cast shadows in the shape of crosses.

The fourth station — Jesus meets his mother — is tender and light. A splash of white and yellow rises from the ground as if to hold the pair up. DeGrazia framed the embracing mother and son with flowers.

At the start of the DeGrazia stations, Christ shoulders his large cross. “He’s carrying the weight of the world. He’s carrying the weight of us, the sinners,” DeGrazia said.

In later stations, the cross nearly overcomes Jesus and his body begins to contort under its burden.

The series ends with the Resurrection, a nontraditional station DeGrazia chose to add. The church acknowledges 14 traditional stations, ending with Christ’s burial in the tomb. Some modern prayer books now include the Resurrection and St. John Paul II added it in 1991 when he led the Way of the Cross at the Colosseum in Rome.

DeGrazia said he didn’t consider the Way of the Cross complete without the risen Christ: “To me this is the way the Way of the Cross should end, with Christ risen. Alleluia.”

Angels, dancing children and a Yaqui deer dancer celebrate Christ in glory in the Resurrection painting.

DeGrazia’s paintings of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection are exhibited each Lent and for a few months after Easter at the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun. This year the gallery also is showing several of his depictions of Our Lady of Guadalupe. His paintings of Father Kino are part of the permanent exhibit.

The mission chapel sits adjacent to the gallery. Its walls are decorated with DeGrazia’s interpretations of Father Kino, Mary and St. Juan Diego. There also are paintings of angels and Indians. On top of adobe bricks, sit mementos, crosses, pictures and other items left by visitors.

In their biography, the Johnsons called the painter a “complicated man” who had once described himself as “not saint nor devil, but both.”

DeGrazia was known to favor booze and carousing and to have a weakness for women. He also displayed a charitable side, giving paintings to people who could not afford to buy original artwork. He often gave rights to his art to charities for fundraising.

His biographers portray him as individualistic, down-to-earth, raw, intensely private and complex.

DeGrazia was born in 1909 in Morenci, Arizona. His Italian immigrant parents named him Ettore. Later he was called Ted. The family lived in the copper mining town for much of DeGrazia’s early life. They left for Italy in 1920 and stayed five years, returning to Morenci when Ettore was 16.

The Johnsons’ book said that DeGrazia stopped participating in church life as a young man, after two Italian monks dragged him out of Mass for not pumping the organ properly during a service.

A struggling art student, DeGrazia went on to achieve success as an impressionistic painter, making millions from his artwork. His paintings were popular but critics and traditional galleries were not among his admirers.

He traveled frequently in the Southwest and in Mexico. Southern Arizona remained DeGrazia’s home until his death.

Native Americans became his favorite subject. Through them, DeGrazia discovered a kinship with Father Kino. DeGrazia said he prayed to Father Kino and talked to him “like an equal.”

In 1961 the Arizona Historical Society published a book of DeGrazia’s paintings of Father Kino and a copy was sent to the Vatican. The Holy See responded with an apostolic blessing from St. John XXIII and a letter that said the pope saw in the album “touching evidence of filial loyalty and devotion.”

“I’ve always loved him,” DeGrazia said of Father Kino. “Padre Kino had a beautiful personality. He did everything for others.”