by Moira Cullings

moira.cullings@theleaven.org

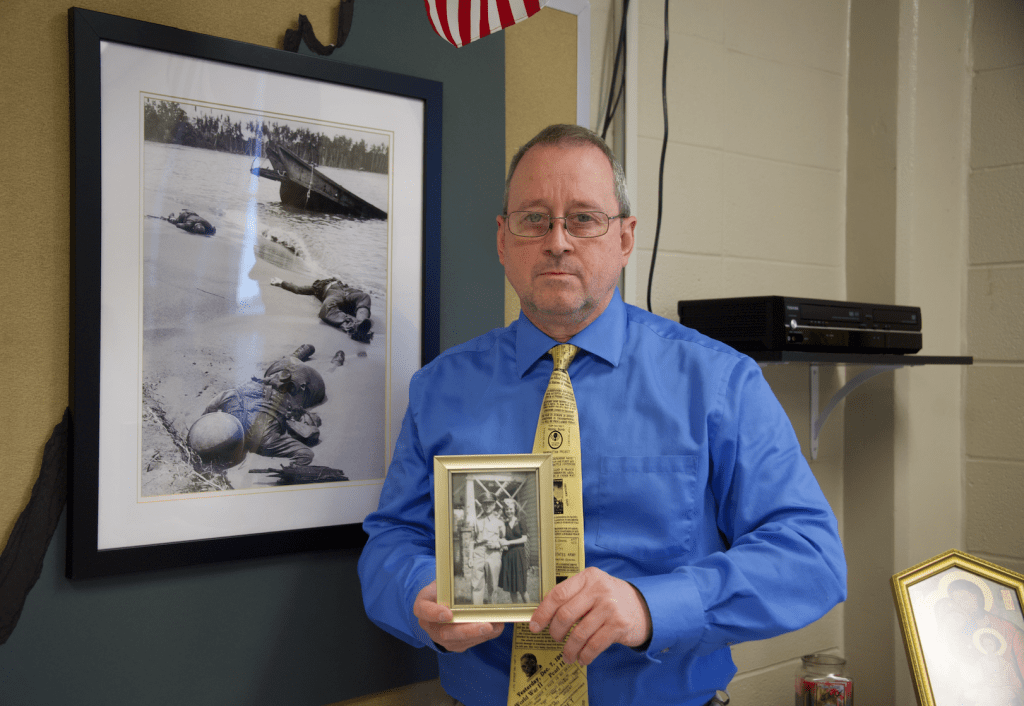

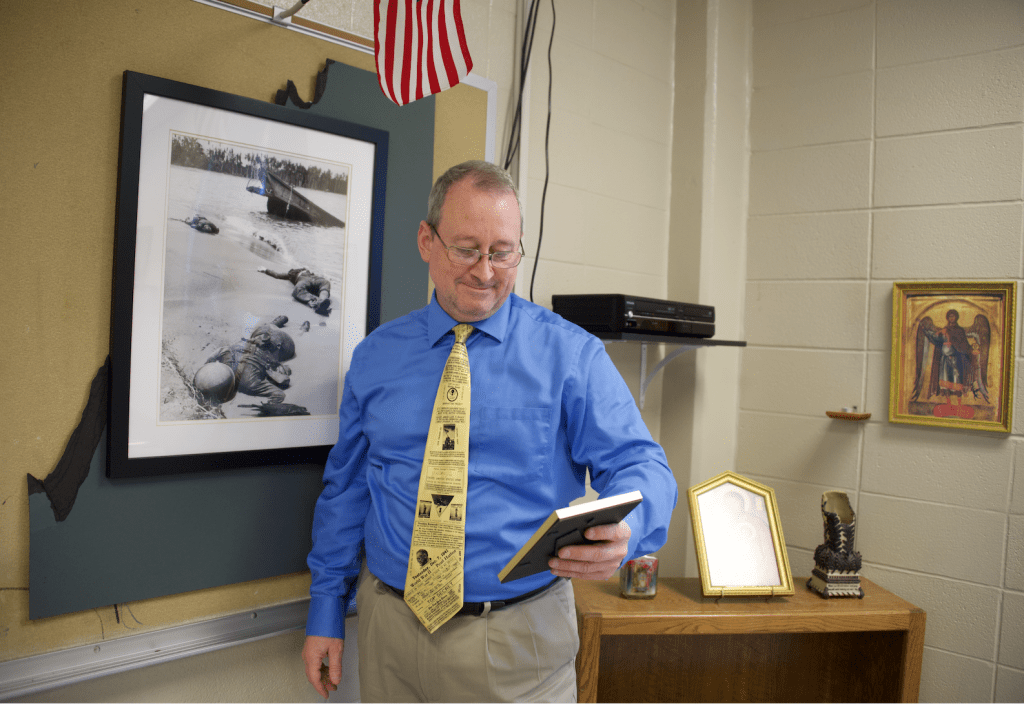

OVERLAND PARK — The most profound lesson Leo Brown instills in his students at St. Thomas Aquinas High School here is hanging on his wall.

Below a crucifix and an American flag is a framed photograph originally published in Life magazine.

It portrays three U.S. Army soldiers lying dead on Buna Beach in Papua New Guinea during World War II in 1943.

It reminds Brown of the lines at the end of “Saving Private Ryan,” when Capt. John Miller tells Pvt. James Ryan to “earn this” after he and his fellow soldiers sacrificed their own lives to save his.

“In other words, we’ve given our lives for you,” said Brown. “Go live a life worthy of this.

“And so, the message for our country and for our faith that I try to communicate with my students is that the freedoms we enjoy are because of these three guys on this beach — times thousands.”

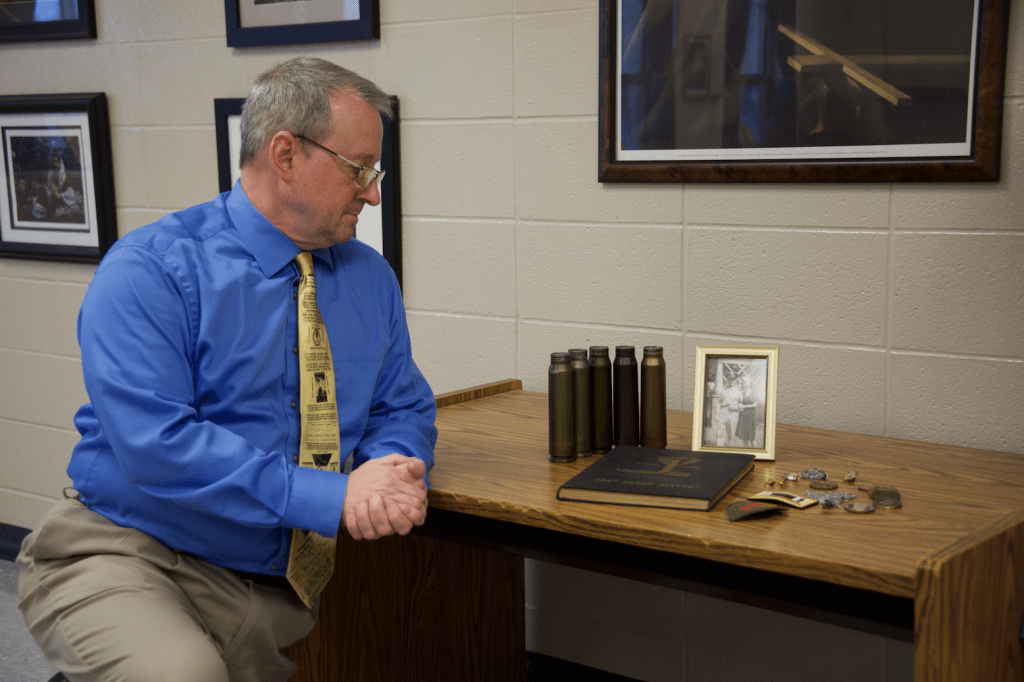

Brown, a senior master sergeant with the U.S. Air Force Reserve, has taught theology at Aquinas for 23 years. During that time, he’s completed two deployments.

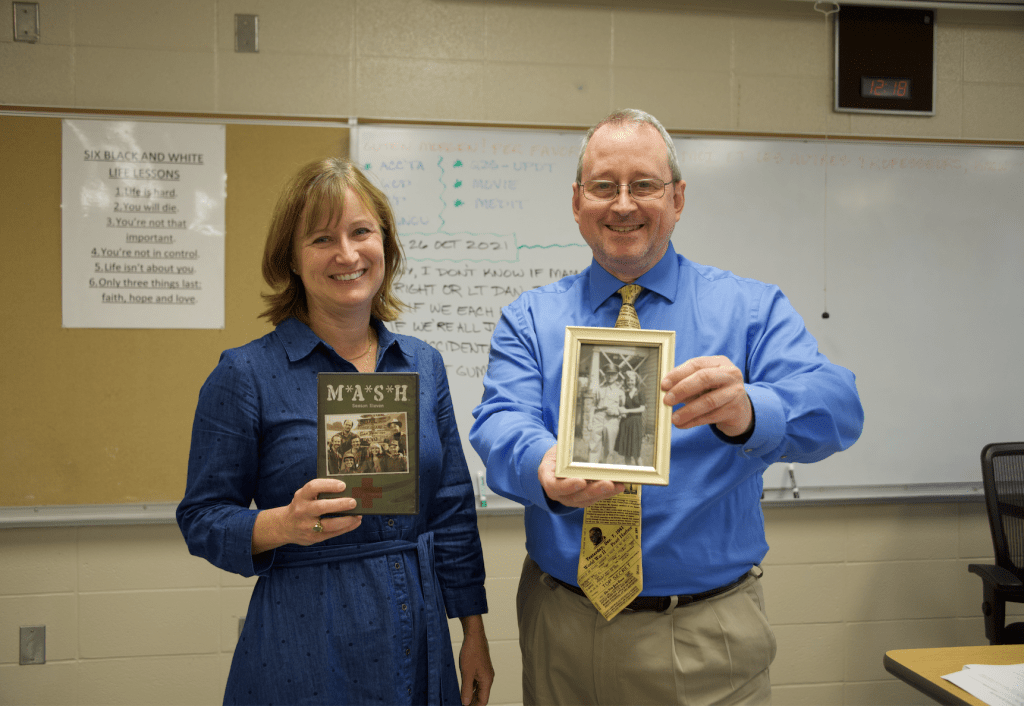

Two other Aquinas teachers — Andrew Lee, English, and Kathleen Mersman, social studies — also served in the U.S. military.

The messages they share as the country prepares to celebrate Veterans Day on Nov. 11 are pertinent to all.

Lessons from the MASH

Growing up with a dad in the military inspired Mersman to join the Army.

“My dad was a 30-year officer in the Military Police Corps,” she said. “He did three [combat] deployments. I was impressed with that and what I saw of military life.”

After high school, Mersman received a Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) scholarship and went to college.

But much had changed between her high school years during President Ronald Reagan’s administration and her college years when President Bill Clinton was in office and the military was being downsized.

“A lot of people in college with me in ROTC were disappointed to discover they ended up going straight to reserve,” said Mersman. “They were looking forward to active duty.

“[The situation] changes depending on the needs of the military.”

After graduating, she owed eight years of service and was on active duty as a lieutenant in the Army Medical Service Corps for four of those years.

“The cool thing was I got assigned to a MASH [unit], like the TV show,” she said.

The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital at Fort Riley, where Mersman was stationed, looked a little different from the 1970s TV program, since by that time it was the early ’90s.

“That was a really interesting job because the Army had actually decided that the MASH was not a particularly useful size anymore,” she said.

Mersman’s job as a supply officer was to give away equipment to other hospitals and units.

The MASH also contained an emergency room, and one of the most astonishing things she witnessed was young people, who had been goofing off the day before, bravely take on high levels of responsibility.

“You’d watch these people who were kids who seemed so immature,” she explained, “but then, all of a sudden, they’re handling this life and death situation with grace and poise and confidence.

“That always inspired me.”

Rising to the occasion

Lee’s time in the Navy was a period of self-discovery.

“I think you really learn about yourself,” he said, “[and] you learn about people from other parts of the United States.

“Some of the people I served with came from wealthy families, and some people came from the option of going to jail or not.”

Lee also grew up with a dad in the military. He decided to participate in the Air-Sea College Program, which required two years of active duty and four years reserve, right after high school.

He completed boot camp in San Diego before beginning an airman apprenticeship training and reporting to duty.

He was stationed on the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt.

“While I was there,” he said, “we did about three tours between different parts of the world, mainly the Caribbean, the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

“My responsibility was to help move aircraft to and from the flight deck using the elevators and doing fire watches for the hangar deck.”

Although being in the middle of the ocean wasn’t as dangerous as other assignments, Lee served during the Cold War and had encounters with Soviet aircraft flying over the aircraft carrier to take pictures.

Like Mersman, he witnessed young people step up to the plate when challenges surfaced.

“You’ve really got that camaraderie that you’re not going to find in other settings,” he said. “That was an important aspect that you don’t necessarily get in the civilian world.”

A powerful journey

Brown was two days into his Afghanistan deployment when he received a taste of the danger lurking outside Bagram Air Base where he was stationed.

It was a Sunday and, thanks to a Catholic chaplain, he was attending Mass.

“We had a false rocket attack that night,” said Brown. “I spent the first part of Mass laying in a ditch with two Polish military members.”

Brown said that having a chaplain on his deployments provided a sense of comfort and familiarity.

“Knowing that those chaplains and their assistants were around offering everything from a friendly ear to the sacraments to some Bible studies was huge for me,” he said. “That’s not to be taken for granted.”

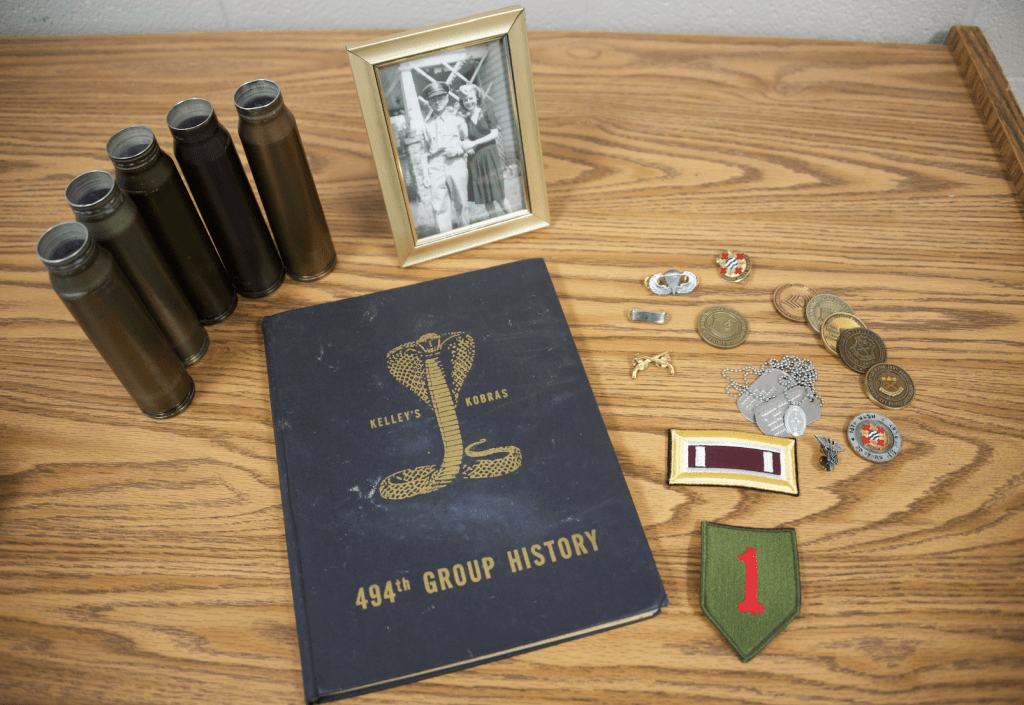

Like Lee and Mersman, Brown looked up to his dad, who served during World War II.

He joined the Air Force after college and was on active duty from 1988-1992. In April 2001, he joined the Air Force Reserve, a role he will hold for around three more years.

Brown initially served as a public affairs specialist and worked as a journalist before becoming a first sergeant. In that capacity, he helped his commander in multiple ways with the goal of maintaining the morale of their unit.

“You are with people at the very worst and very best times in their lives,” he said. “I had to do a death notification with the commander and the chaplain. I was also involved with retirements and promotions.”

Brown completed two deployments during his time as a first sergeant — the first to Afghanistan from March to October of 2014 and the second to Kuwait from January to April of this year.

One of his favorite moments happened in Afghanistan when he was talking with an Air Force doctor who was a spinal surgeon.

“He said they found an Afghan girl who had horrible scoliosis in the village [outside of the base],” said Brown.

The doctor performed a surgery to straighten her back out.

“He said the mom and dad were floored,” said Brown. “He said people were just overcome.”

Fighting for good

Lee and Mersman said watching the coverage of the U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan this past August was frustrating.

But Brown said he focuses on the success stories he experienced there.

“We’re not there right now,” he said, “but I’m convinced from when I was there those seven months that we did do some good things.”

Lee agreed.

“You’ve got people who grew up in an American occupation that were hopefully given opportunities,” he said. “And hopefully that taste of freedom will live with them and give them hope for whatever they have to deal with.”

Mersman said she worries that because the U.S. no longer has mandatory service and there is not currently a draft, people have become more detached from the military.

“If you go back to Vietnam, Korea, even during the early ’50s Cold War, everyone had someone [they loved] in the military,” she said. “You understood what the risks and the costs were, and you paid attention.

“There’s less paying attention now.”

The three teachers pass on stories with their students so that veterans’ sacrifices are not forgotten.

“Whether somebody does two years or 20 years or 30 years, everybody’s got their piece in this,” said Brown. “Everybody has a story.”