by Moira Cullings

moira.cullings@theleaven.org

ATCHISON — Catholics have made their mark on scientific discoveries for centuries.

Now, Dr. Christopher Shingledecker can count himself among them.

An assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Benedictine College in Atchison, Shingledecker was part of a group of scientists who recently discovered new molecules in interstellar space.

“I never expected to be involved in such a big discovery,” he said. “It’s really been a remarkable experience.”

An ‘unusual’ discovery

Shingledecker earned his bachelor’s degree and Ph.D. at the University of Virginia.

After receiving the latter in 2018, he was awarded an Alexander von Humboldt postdoctoral research fellowship and relocated with his wife to Munich for two years.

There, he worked at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, which, he clarified, relates to the physics of outer space — not to aliens.

After his work wrapped up, he knew what he wanted to do next.

“I always wanted to [teach] at a Catholic liberal arts college — it was my goal all throughout school,” he said.

It was easy to narrow down his choices. The only one in the United States with an astronomy major is Benedictine.

Shingledecker started as an assistant professor at the college last fall.

For the past two years, he was also fulfilling another dream — working on the Green Bank Telescope Observations of TMC-1: Hunting Aromatic Molecules (GOTHAM) team.

The group is led by Dr. Brett McGuire, assistant professor of chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), who Shingledecker has worked with over the years.

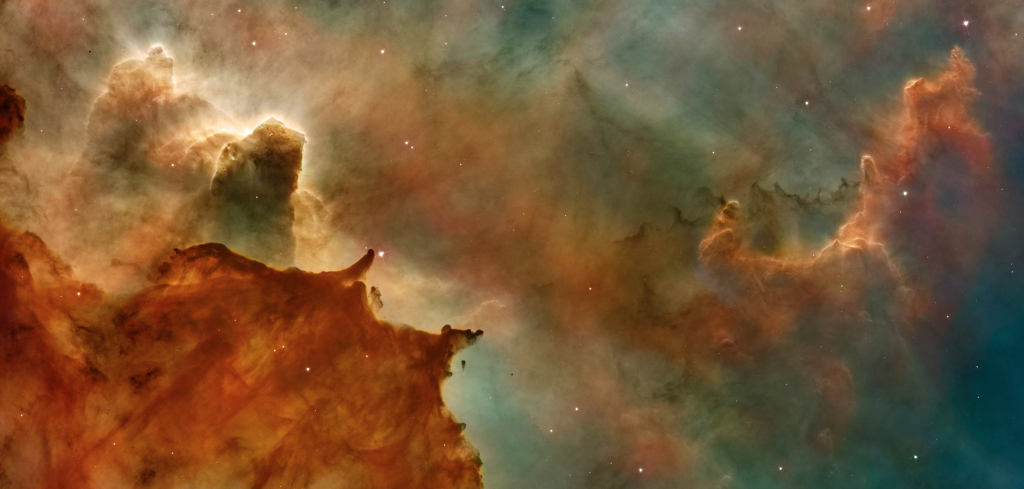

“This GOTHAM project really grew out of some interesting discoveries that we were making in a particular region of space — the molecular cloud called TMC-1,” said Shingledecker.

The team’s research culminated in the discovery of a vast reservoir of new aromatic material in TMC-1, which the scientists found using the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia — the largest steerable radio telescope in the world, said Shingledecker.

They detected two polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are the first molecules of this type ever specifically identified in space.

Very small specific molecules containing two, three and four atoms have been detected in space for a long time, but PAHs are much more complex, and they’re what scientists have suspected were behind IR emissions for years. But IR can’t identify a specific PAH molecule, and radio can, and it’s now provided unequivocal proof that PAHs exist in space.

“It’s really unusual where we saw them — this cloud TMC-1,” Shingledecker explained, “because it’s rather cold compared to some of the places where we might look.

“It’s a little bit like seeing a palm tree in Antarctica. You may not be surprised that there are palm trees, but you may be surprised that there’s one in Antarctica.”

The discovery elicits more questions, like what implications it has for the role large carbon molecules play in forming stars and planets.

It also raises the question of how the molecules themselves were formed. As GOTHAM’s chief theorist, Shingledecker seeks to understand exactly that.

Overall, the discovery is simply “startling,” he said, and will likely prompt greater research into the origins of life.

Stephen Minnis, president of Benedictine, expressed how proud the college is of Shingledecker’s achievement.

“We were very pleased to be able to bring Dr. Shingledecker to Benedictine College and are excited to see his success,” he said, “which includes this major research study and tremendously important discovery.

“His work and that of others in the sciences, along with the construction of the Daglen Observatory and expansion of Westerman Hall [at Benedictine], are great illustrations of why Benedictine College is becoming known as the Catholic college for STEM education.”

‘The avalanche is about to start’

When Dr. Louis Allamandola heard about GOTHAM’s discovery, he was elated.

A leading expert on PAHs, he was one of the first to suggest their existence some 30 years ago.

Proving these molecules exist is an important breakthrough for further research, which was previously hindered by doubts about their presence, said Allamandola.

“[With] the discovery of this, the dam has finally broken,” he said. “The avalanche is about to start.”

Allamandola hails from New York and currently lives in California, where he developed an astrochemistry laboratory at NASA’s Ames Research Center.

A product of Catholic schools from elementary to undergrad, he, like Shingledecker, never expected to have such a significant impact on the world of science.

“It’s all God’s plan somehow,” he said.

Years ago, Allamandola built a laboratory at Leiden University in the Netherlands that simulated conditions in deep space with extremely low temperatures.

In these laboratory simulations of interstellar space, he made ices, irradiated them with ultraviolet light and studied what kinds of molecules were created as a result.

What’s special about GOTHAM’s discovery, said Allamandola, is that the complex molecules they found exist inside dense interstellar clouds where dust particles shield them from UV radiation and prevent them from being blown apart.

It’s a satisfying clarification for his life’s work, and one of many major strides that have been taken in astrochemical research since he started his career.

“In those days, space was thought to be totally barren,” he said. “Temperatures were way too low. Ultraviolet was so harsh. In the interstellar space, chemistry was thought to be a nonstarter.”

Now with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope set to launch soon, Allamandola predicts “we’re going to see these PAHs all over the universe.”

A universe ‘beyond belief’

Several of the world’s experts in space research have something special in common — an unwavering faith in God.

The Society of Catholic Scientists, of which Allamandola and Shingledecker are members, is a growing organization that connects scientists of faith.

Its mission “exists to foster community among Catholic scientists, to bear witness to the compatibility — and indeed, mutual benefit — of science and Catholic faith and to provide a platform for Catholic students to interact with more senior Catholic scientists,” said director Dr. Karin Oberg, a professor in the Department of Astronomy at Harvard.

She said her work has never caused any doubts about God’s existence.

“Rather, my Catholic faith is a source of meaning when pondering the scientific projects that I pursue, knowing that it is his creation I am exploring,” she said.

It’s also “a source of confidence in the fundamental intelligibility of the cosmos, and a source of strength in my daily work trying to help [educate] the next generation of scientists,” Oberg added.

Shingledecker’s work has also strengthened his faith, and the chance to share that with the Benedictine community is special.

“I love the students here,” he said. “They’re fantastic. And it’s really lovely to be able to show them that faith and reason go together.”

Shingledecker, who draws inspiration from Albert the Great, the patron saint of scientists, enlightens his students on the church’s support of astronomical research throughout history.

“The church has preserved knowledge [and] promoted learning, schools and science. And for it to be seen as suddenly antagonistic to [scientists] is a betrayal of the legacy of the church in fostering learning and discovery,” he said.

Allamandola agreed.

“Even though you hear over and over and over again that science discredits religion, the truth is the opposite,” he said. “[Many] of the great scientists historically believed in God.”

Studying the universe and “how it all hangs together” has only increased Allamandola’s faith.

“When you see the beauty out there, you realize how we’re just super amateurs,” he said. “It’s thrilling and exciting to see God’s mastery and the intricacy.

“How it all goes together is beyond belief.”