by Michael Podrebarac

Special to The Leaven

Prelude

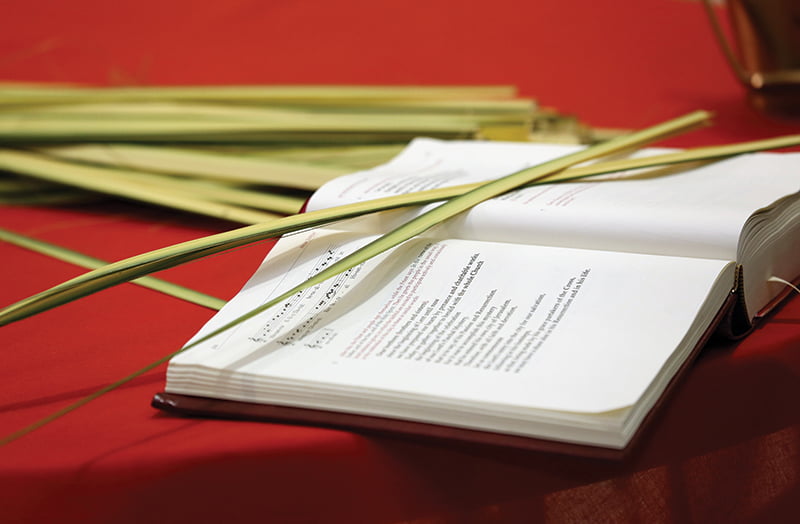

Just as the crowds of Jerusalem gathered at the city gate and welcomed Jesus with praises, even paving his way with the fronds of palm plants and olive branches, so did the later Christian congregation of the city do the same as their bishop — representing Christ — rode into the old part of the city on a young colt. Still today, we bless and keep these palm fronds as a reminder that, just as the Lord was welcomed into Jerusalem, so we welcome him into our parish churches and acclaim him our king.

Now, a few words about what it means to commemorate an event, especially in our liturgical prayer. We are not reenacting the event, nor pretending that we are of the same mindset as those who experienced the events as they first took place.

No, we enter our commemoration with our faith that Jesus indeed is Lord, that he died and rose from the dead, and that he is our Savior. We make use of the various rituals of Holy Week to imitate the essence of what took place in salvation history, not to simply stage some sort of dramatic production.

Unlike the disciples and the other original followers of Jesus, we know the end of the story!

Holy Thursday

The whole “theme” of the liturgy of the Paschal Triduum — which is, in fact, one single liturgy celebrated over three days — is the triumph of Jesus in his Paschal Mystery: Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again!

And so, the liturgy begins, even on Holy Thursday, with the entire Paschal Mystery in mind.

On each of the “days” of the Triduum (a word which simply means “three days”), however, we do commemorate different moments in the Lord’s life and ministry, each of which contributes to the larger whole.

“[Jesus] rose from supper and took off his outer garments. He took a towel and tied it around his waist. Then he poured water into a basin and began to wash the disciples’ feet.” (Jn 13:4-5).

Now, it is true that Holy Thursday commemorates the institution of the Eucharist and the sacrament of holy orders, which makes possible the Eucharist for every generation. The second reading makes this clear.

But the first reading, the Passover account, sets the Eucharist in the context of the larger mystery. Whereby death passed over the Hebrews on their night of deliverance, so death also passes over us as we experience redemption in Christ.

And the Gospel reading reveals the difference our salvation is to make. The ancient Hebrews would go on to fight and struggle against their enemies for many years. We who have been saved by Christ are not to fight against one another, but to wash one another’s feet.

Although this rite, in which the priest washes feet in order to show his solidarity with the humility and service of the Lord Jesus, was not explicitly incorporated into the Holy Thursday service in Jerusalem, Egeria does mention it as a practice among Christian believers.

Only in recent times has it come into the liturgy to signify what it means to be great among others: “Do you realize what I have done for you? You call me ‘teacher’ and ‘master,’ and rightly so, for indeed I am. If I, therefore, the master and teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to wash one another’s feet. I have given you a model to follow, so that as I have done for you, you should also do” (Jn 13:12b-15).]]

Good Friday

There are no words nor songs that commence the second part of the Triduum liturgy, the Good Friday celebration of the Lord’s passion. No words could equal the solemnity of the moment when the priest and ministers enter and prostrate themselves before a sanctuary stripped of everything save its essential furniture, just as Jesus was stripped of everything save his essential being as Son of God and Son of Man. The people kneel in this moment without words.

Egeria described a moment in the gathering of the faithful on Good Friday in which a silver casket was presented to the bishop of Jerusalem. The box contained what was believed to have been a portion of the very cross upon which Jesus was crucified, as it had been discovered by St. Helena, the mother of the first Christian Roman emperor Constantine.

After the bishop removed the relic of the cross and placed it on a table, with ministers standing on either side with lighted torches, the faithful would come and venerate the relic, usually with a kiss. “But may I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Gal 6:14).

The Easter Vigil

In reality, the entire three days — even the entire week — was a continuous vigil for those early Christians in Jerusalem as they went from place to place, remembering what had taken place at these locations during the last week of Jesus’ life on earth.

But the greatest of vigils, in fact, what came to be known as the “Mother of All Vigils,” was reserved for Saturday night through Sunday dawn.

“This is the night!”

Thus cries out the singer of the Easter proclamation as the Passover recorded in the Book of Exodus and read aloud on Holy Thursday now becomes the core theme of the Easter Vigil on Holy Saturday night. The fire that is blessed signifies the light that “shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” (Jn 1:5). It is a light “divided yet never dimmed,” the singer continues, as the paschal candle and the individual tapers of the faithful illumine the church.

This is the night of redemption, signified in the blessing of the water, the baptism of the catechumens and the renewal of the baptismal promises by all the faithful. As the Israelites passed through the parted Red Sea on dry land and were not drowned, so the Christian passes through the waters of baptism, not drowned, but dying nonetheless to sin and death and rising to new life through Christ’s death and resurrection.

The deliverance of Israel through water and the deliverance of the white-robed baptized through water is renewed for all as the priest sprinkles the faithful with the same saving water. Catholic Christians throughout the world restore the Alleluia to their liturgical and devotional prayers at Easter. Christ has died and has risen. Alleluia: “The Lord be praised.”

From the entrance into Jerusalem, to the Passover feast, to the Garden of Gethsemane, to the high priest’s court, to the praetorium of Pilate, then along the suffering streets of Jerusalem, to Golgotha and the borrowed tomb, to the brightness of the angelic presence at the same tomb, now departed and empty: These are the stations of redemption, commemorated and signified by the stations of the sacred liturgy of Holy Week, celebrated long ago in Jerusalem, discovered by a Christian pilgrim and echoed in the hearts of all Christians.

Thanks be to God, alleluia, alleluia.

* Michael Podrebarac is the archdiocesan consultant for the office of liturgy and sacramental life.