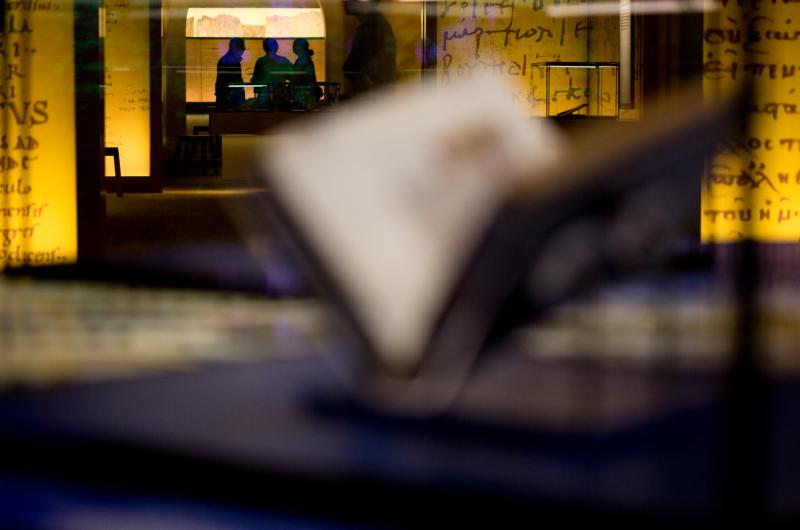

People stand near a bound book and biblical codices inside the “History of the Bible” exhibit at the Museum of the Bible in Washington Nov. 15. (CNS photo/Tyler Orsburn)

by Mark Pattison

WASHINGTON (CNS) — Hey, Smithsonian, there’s a new kid on the block.

It’s the Museum of the Bible, just a few blocks from the National Mall in Washington. With its opening to the public Nov. 18, it will tell visitors how the Bible — both Old Testament and New Testament — has intersected society and at times even transformed it.

The people behind the museum say that if visitors were to read the card behind every artwork, saw every video, heard every song and took part in every interactive experience — including a Broadway-style musical called “Amazing Grace” about the song’s writer, John Newton, and the biblical inspiration behind the abolitionist movement — it would take them 72 hours to do it all.

But visitors can take their time, because there is no admission charge to the museum.

The museum was the brainchild of Steve Green, chairman of the museum’s board of directors and president of the Hobby Lobby chain of arts and crafts stores. It was Hobby Lobby that successfully argued before the Supreme Court in 2014 that, as a closely held company, its owners based on their religious beliefs should not have to comply with a federal mandate to cover all forms of contraceptives because some act as abortifacients.

“It’s exciting to share the Bible with the world,” Green said at a Nov. 15 press preview of the museum, which is just one block from a subway stop serving three of the Washington-area subway system’s six lines.

The $500 million museum had its coming-out party in 2011 at the Vatican Embassy in Washington before a gathering of business, government, academic and religious leaders.

Museum backers found a circa-1923 refrigeration warehouse that had been repurposed for other uses, bought the building and set about expanding it, adding two stories and a skylight to the top of the structure and a sub-basement for storage space.

The result: six floors of exhibits, not to mention the theater, gift shop and restaurants.

Most of the exhibits, when necessary, use the designations “B.C.” and “A.D.” — Before Christ and Anno Domini, Latin for “year of the Lord” — to refer to the timeline of civilization marked by Jesus’ birth. Museum brass had discussions on the topic, Susan Jones, curator of antiquities for the museum, told Catholic News Service. “They decided that’s the way they wanted to go,” she said.

Most researchers, Jones noted, prefer the designations “B.C.E” and “C.E.” — Before the Common Era and Common Era — because “they’re more neutral.” Also preferring the latter names is the Israeli Association for Antiquities, which has a 20-year deal with the museum to supply artifacts in a fifth-floor exhibit space. “You’re in Israel now,” she told a visitor as a tour guide was boasting that he had his hand on a rock from the Western Wall in Jerusalem in the exhibit.

There are a number of items on loan to the museum from the Vatican Museums and the Vatican Library. They’re in a tiny space on the museum’s ground floor — relatively speaking, since the museum totals 430,000 square feet. What can’t be seen in person can be accessed by two dedicated computers in the exhibit area, one for the museums and one for the library.

Brian Hyland, an associate curator for medieval manuscripts at the museum, told CNS the Vatican donations will be around for six months, then replaced by other artifacts. One of his favorite items currently in the exhibit space is the first volume of a facsimile of the Urbino Bible, which dates to the 15th century; the second volume will replace the first volume at some point in 2018.

Despite the Bible’s status as the best-selling and most-read book in history, one exhibit speaks of “Bible poverty,” and the fact that roughly 1 billion people have never read the Bible in their native tongue.

An organization called IllumiNations, a collaborative effort by Bible translation agencies, is trying to change that. The aim is to have, by 2033, 95 percent of the world’s peoples with access to the full Bible, 99.9 percent with at least the New Testament, and 100 percent with at least some parts of the Bible translated into what museum docent William Lazenby called “their heart languages.”

The exhibit space touting this endeavor is stocked with Bibles and New Testaments in various languages. Hardcover books with blank pages in the exhibit represent the untranslated languages. Wholly untranslated languages are represented by yellow covers, and partially translated tongues are represented by covers with a redder hue.